Jemar Tisby’s recent book The Color of Compromise is a call to the American church to wrestle with its involvement in slavery, segregation, and racism.  As the recipient of an MDiv from Reformed Theological Seminary and a PhD candidate in history at the University of Mississippi, Tisby is uniquely positioned to bring a Christian perspective to the discussion of America’s religious and racial history. While this work is an important read for anyone concerned with racial justice and should provoke introspection and lament, it also merits careful evaluation in light of how it frames the discussion of racism and complicity.

As the recipient of an MDiv from Reformed Theological Seminary and a PhD candidate in history at the University of Mississippi, Tisby is uniquely positioned to bring a Christian perspective to the discussion of America’s religious and racial history. While this work is an important read for anyone concerned with racial justice and should provoke introspection and lament, it also merits careful evaluation in light of how it frames the discussion of racism and complicity.

The Color of Compromise can roughly be divided into two sections. The first 9 chapters present an overview of race through the first four centuries of American history, beginning with the arrival of Africans in Jamestown, and continuing though the institution of chattel slavery, the Civil War, Black Codes, Jim Crow laws, the victories of the Civil Rights Movement, and the rise of the Religious Right during the 70s and 80s. Historical events are intertwined with historical theology, as Christians attempted to justify or repudiate slaveholding and segregation. Although commentary and interpretation is interspersed throughout the book, its presence becomes much more marked in Chapters 10 and 11, which discuss contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter and provide guidance for how evangelicals should pursue racial reconciliation.

Why bother with history?

Many may question why such a book is necessary, perhaps even suggesting that a discussion of America’s racial history is inherently divisive. I think this response is mistaken. Knowledge of our racial history helps us to better understand the present, particularly given the historical proximity of some of the relevant time periods. For example, Ruby Bridges, who faced death threats as a six-year-old for being the first black child to attend her all-white elementary school in New Orleans, turned sixty-four last year. A black woman who was in my Bible study attended a segregated school as a child. Not only are these events preserved within the memories of people who are still alive, they live on in residential and school segregation, much of which can be attributed to now-illegal redlining practices that produced concentrated black urban poverty during the 1960s and 1970s.

An understanding of history also helps us to better empathize with our black brothers and sisters in Christ. In his book Woke Church, Dr. Eric Mason, a black pastor from Philadelphia, recounts how he heard stories about Klan terrorism and racial hatred from his grandparents. These stories and his own encounters with racism pushed him away from the “white man’s religion,” until he came to faith in college. If we’ve rarely experienced racial hatred, we’re likely to view these stories as aberrations or -worse- exaggerations. Recognizing instead that racism is a real part of our nation’s past and present helps us to respond with sensitivity and gentleness.

How bad was it?

In a short review, I don’t have space to summarize the history of race in America. Instead, let me offer just one example of a particularly horrific 1904 lynching recorded by Tisby:

The lynching … was planned for … a Sunday afternoon after church so a larger crowd could gather. The murderers strategically chose their location for maximum intimidation of the black populace…. More than a thousand people showed up to gawk at the lynching of Luther and Mary Holbert. The lynchers tied up the Holberts and commenced with ‘the most fiendish tortures.’ First, the white murderers cut off each of he fingers and toes of their victims and gave them out as souvenirs. Then they beat the bodies of Luther and Mary so mercilessly that one of Luther Holbert’s eyes dangled from its socket… ‘The most excruciating form of punishment consisted in the use of a large corkscrew in the hands of some of the mob. This instrument was bored into the flesh of the man and woman, in the arms, legs, and body, and then pulled out.’… They burned Mary first, so Luther could see his beloved killed. Then they burned him. (p. 107)

What was the legal response?

Woods Eastland, who led the mob that lynched the Holberts, did face charges in the murders, but his acquittal was a foregone conclusion. After the all-white jury found him innocent, Eastland hosted a party on his plantation to celebrate. (p. 108)

When I first read this account, I was both appalled and shocked. These murders took place not in some remote corner of Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, but in Mississippi. How could that be? My horror was appropriate, but my surprise was not. As a Christian, I ought to know the depths of the evil that lurks in every human heart and the way in which sin permeates entire societies. I was surprised only because I had subconsciously exempted my own country from the Bible’s analysis. Like every nation’s history, ours is a mixture of good and evil, nobility and infamy. To admit this fact is not to repudiate the love or allegiance we appropriately feel for our country, but rather to insist that every nation be held accountable to God’s ultimate moral authority.

Where was the church?

As troubling as racism and racial terrorism is, the church’s response to these realities will be even more troubling to most evangelicals. Tisby acknowledges at the outset that not all Christians supported chattel slavery, yet the brights spots are few and far between. Respected theologians like Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield owned slaves. The Southern Baptist Convention was created to oppose the Northern Baptists, who bristled at the idea of sending slave-owners to be missionaries. Likewise, the Presbyterian and Methodist churches split over slavery in the decades prior to the Civil War. Even after slavery was outlawed, racism persisted in both the north and the south. For example, the African Methodist Episcopal Church was created after black church members were physically forced out of their seats during prayer to make room for whites (p. 53-54).

Tisby characterizes evangelical attitudes towards the Civil Rights Movement as less overtly racist, but tepid. For example, Billy Graham “personally took down ropes segregating black and white seating in the audience” at a 1953 rally, but “held back from actively pushing for black civil rights… Like many evangelicals, Graham believed race relations would gradually improve – one conversion and one friendship at a time” (p. 135). While Martin Luther King, Jr. and other predominantly black civil rights leaders pushed for direct action and non-violent protest to tear down unjust laws and practices, evangelicals urged litigation and incrementalism: “They were overly cautious when the circumstances demanded a measure of outrage and courageous confrontation.” (p. 137) This hesitancy was only exacerbated by civil unrest that erupted over the course of the next few decades. While leaders like Graham saw the “unraveling of the fabric of the nation” (p. 142), King insisted that “social justice and progress” are the only absolute prophylactic against the violence that he abhorred (p. 143). This divide between white racial moderates and black civil rights leaders would continue beyond the civil rights era into the policies of Nixon and Reagan, who both appealed to “law and order” as a remedy for social ills. Tisby argues that evangelical support for the Moral Majority similarly created distance between white and black Christians: “The Religious Right’s own statement of political objectives also demonstrates its troubling compromise with racism by promoting policies that failed to advance or support black civil rights.” (p. 170)

Summarizing the book’s first nine chapters, Tisby concludes that “after more than three centuries of deliberate, systematic race-based exclusion, the political system that had intentionally disenfranchised black people continues to do so, yet in less overt ways. Simply by allowing the political system to work as it was designed –to grant advantages to white people and to put people of color at various disadvantages– many well-meaning Christians were complicit in racism.” (p. 171)

Is critique permissible?

Before turning to the remainder of the book, I have to ask an odd but genuine question: is criticism permissible? In the first chapter, Tisby makes an important statement, which I’ll quote at length:

“The people who will reject this book will level several common objections. What stands out about these complaints is not their originality or persuasiveness but their ubiquity throughout history. The same arguments that perpetuated racial inequality in decades past get recycled in the present day. [Critics] will claim that a Marxist Communist ideology underlies all the talk about racial equality… They will assert that the historical facts are wrong or have been misinterpreted. They will charge that this discussion of race is somehow ‘abandoning the gospel’ and replacing it with problematic calls for ‘social justice.’ After reading just a few chapters, these arguments will sound familiar. These arguments have been used throughout the American church’s history to deny or defend racism.” (p. 21)

Statements like these make me hesitant to engage in even the gentlest criticism because Tisby has framed the discussion in terms of a strict dichotomy between reformers working for justice and critics working to “deny or defend racism.” No matter how adamantly we support Tisby’s conclusions, it’s dangerous to accept his characterization of this issue, which leaves no real room for sincere disagreement. We should certainly be willing to examine our own hearts and interrogate our motives. But we must not allow the desire to be on the “right side” of Tisby’s admonitions overwhelm our commitment to careful reflection and rational deliberation.

Past and Present

A common refrain in The Color of Compromise is the statement that “racism changes over time… racism never goes away; it just adapts” (p. 19, c.f. p. 110, 154, 155, 160, 171). This claim is important for Tisby’s project because it allows him to conflate actions and attitudes that are, on the surface, quite different. For example, a Christian who was “complicit in racism” in the early 19th century would have endorsed chattel slavery and may have believed that blacks were an inferior race of men under “the curse of Ham.” A Christian who was “complicit in racism” in the mid-20th century would have supported segregation and opposed interracial marriage. Now consider how Tisby characterizes “complicity” in the modern era:

Christian complicity with racism in the twenty-first century looks different than complicity with racism in the past. It looks like Christians responding to black lives matter with the phrase all lives matter. It looks like Christians consistently supporting a president whose racism has been on display for decades. It looks like Christians telling black people and their allies that their attempts to bring up racial concerns are ‘divisive.’ It looks like conversations on race that focus on individual relationships and are unwilling to discuss systemic solutions. Perhaps Christian complicity in racism has not changed much after all. (p. 191)

A moment’s reflection should give the reader pause because the behaviors that characterize “complicity in racism” over the various centuries are light-years apart. A recognition that racism still exists does not commit us to this kind of false equivalency. A person who says “all lives matter” is not morally comparable to a person who supports kidnapping men and women and chaining them to the hull of a slave ship. If anything, conflating the two minimizes the horrors experienced by those who survived the brutality of slavery.

Consider the parallel example of anti-Semitism or women’s rights. There is no question that anti-Semitism has raged for millennia, from the Inquisitions of Medieval Europe to the pogroms of Russia to the Holocaust. Similarly, women were denied the right to own property or to vote for centuries of American history. Yet it would be incorrect to suggest that “complicity in anti-Semitism” or “denial of women’s rights” are equally prevalent and qualitatively identical among Americans in 2019 as they were among Americans in 1819. It would be even more unjustifiable to argue that the only way to avoid complicity today is to adopt a particular attitude towards Middle Eastern foreign policy or abortion.

I fear that many today are employing this faulty reasoning with regards to race. People are rightly ashamed of America’s racial history and are motivated by this history to do what is right and just. I applaud this zeal. Yet zeal is not a substitute for moral reasoning or appeals to Scripture. If we give carte blanche to anyone waving the banner of antiracism or social justice, we may find ourselves committed to a whole host of ideas and causes whose legitimacy or wisdom we are no longer even permitted to question.

Cancelling Compromise

If we grant that genuine dialogue is permissible and desired, Tisby’s specific proposals are mixed bag. Some should be entirely uncontroversial: advice to “watch documentaries about the racial history of the United States” or to “Diversify your social media feed by following racial and ethnic minorities and those with different political outlooks than yours” (p. 195) is equally applicable to all people. Tisby’s encouragements to “Find new places to hang out” or “Join a sport, club, or activity with people who are different” is particularly relevant to whites because they, as the numerical majority, will necessarily have a more homogeneous social network than minorities.

Other proposals are reasonable, but seem largely symbolic. Tisby’s suggestion to go on pilgrimages to civil rights museums or his call to make Juneteenth a national holiday may raise the profile of antiracism but are unlikely to create large-scale social change.

The real flashpoint comes from Tisby’s support for reparations, which he acknowledges is “the only ‘r-word’ more controversial to Americans than racism” (p. 197). The heated debate over reparations shows precisely why ground rules need to be established: Will Christians assume the best of each other, not imputing hidden agendas and sinister motives to their interlocutors? Is it possible for someone to abhor racism, but to still deny the biblical legitimacy of reparations?

These questions are particularly important given the brevity of Tisby’s argument on behalf of reparations. He appeals to the Old Testament laws and New Testament examples like Zaccheus to argue that the Bible commands restitution in cases of theft (p. 198). Yet given that these passages are speaking about individual sins committed by particular people, one immediately wonders how these passages could be rightly applied to sins that were committed 150 years ago by people and against people long dead. Tisby anticipates this objection but provides only a single paragraph and one bible verse (Daniel 9:8) to support the conclusion that Christianity includes “a sense of [both] corporate and communal participation” (p. 199), thereby justifying reparations.

Opponents of reparations will, understandably, want a more detailed biblical argument than what Tisby provides.

Reconciliation and reparations

Perhaps even more troubling than civil reparations are questions of what Duke Kwon calls “ecclessiastical reparations”, defined as “the obligations that the faithful have to one another in light of historic injustices” (p. 199). Even apart from reparations paid by the state, “the church should be willing to consider some talk about reparations” (p. 199). He appeals to Jesus’ teaching in Matt. 5:24 to argue that the “innumerable offenses [that black people have endured] at the hands of white people in the American church” are “a serious enough sin to interrupt … regularly scheduled worship” so that we that we can “repair the relationship” (p. 199). This language recalls a statement with which the book began: “there can be no reconciliation without repentance” and highlights one of the most profound theological problems with a corporate view of sin, guilt, and repentance.

The New Testament repeatedly insists that Christians have already been reconciled to God and to one another through Christ (Rom. 5, 2 Cor. 5., Eph. 2, Col. 1, 1 Pet. 2, etc.) In contrast, if whites bear corporate guilt for their ancestors’ sins against blacks, then reconciliation is contingent on white repentance. On such a model, I’m left wondering how to explain or process my interaction with black friends. Have I been wrong to assume that our friendship is real? Have we actually been estranged all along because I have never repented of the guilt of my white ancestors on my mother’s side? And if we are not estranged and they have never felt the need for me to repent, then in what sense do we need to be reconciled?

These are serious questions indeed, yet I worry that many evangelicals may brush them aside as thinly-veiled attempts to avoid responsibility and retain privilege. To understand why, we need to take a brief digression into the ideology of critical theory.

Critical theory: a digression

Behind and apart from this particular book, the evangelical church is in the midst of a larger ideological conflict, precipitated at least in part by the election of President Trump. Since 2016, we have witnessed the rapid growth of secular movements grounded in a broad and diverse area of knowledge known as critical theory. Contemporary critical theorists -exemplified by popular scholars like Robin DiAngelo– divide reality into oppressed groups and their oppressors along axes of identity like race, class, gender, sexual orientation, physical ability, age, and so forth. Dominant oppressor groups (men, whites, the rich, heterosexuals) subjugate oppressed groups (women, people of color, the poor, LGBTQ+ individuals) not primarily through physical violence, but through hegemonic power, the ability of dominant groups to impose their values, norms, and expectations on culture.

Moreover, there is solidarity between otherwise unrelated marginalized groups on the basis of their shared experience of oppression. I’ve documented the many ways in which basic Christian doctrine conflicts with the presuppositions of contemporary critical theory, but its approach to truth is particularly relevant.

According to contemporary critical theorists, oppressor groups conceal their bids for power under the guise of “reason” and “objective arguments.” Even when these desires are subconscious, dominant groups are blinded by false ideologies that function to maintain their privilege. In contrast, oppressed groups have special access to truth that enables them to “see through” these specious appeals. Oppressors should therefore recognize their own blindness and defer to the lived experience of marginalized groups.

This basic feature of contemporary critical theory becomes exceptionally important for Christians discussing controversial topics like racism and reparations. Discourse between Christians must non-negotiably be based on two premises: 1) we should assume the best of other believers’ motivations and 2) we should appeal to Scripture as the ultimate, sufficient, and perspicuous authority on all subjects. In contrast, contemporary critical theory would undermine both of these principles, by 1) insisting that privileged Christians are, consciously or unconsciously, motivated by a desire to maintain power and 2) insisting that “objective” appeals to reason, evidence, or even Scripture are unavoidably tainted by privilege.

Why is critical theory relevant to Tisby’s book or this subject? That’s a delicate question.

Critical Theory at The Witness

Given the perniciousness of these ideas, I feel compelled -with significant hesitation- to point out that The Witness, an organization Tisby leads, has seemingly adopted elements of this framework with respect to issues of race. For example, during Black History Month, The Witness ran a series of Tweets, shown below. The prayers for Day 1-3 were “Pray that the Black community (and our friends of color) would be strengthened and filled with hope and joy from the Holy Spirit (Ephesians 3:16, Romans 1:13), “Pray for God to guard the Black community from the enemy as we promote justice (2 Thess. 3:3),” and “Pray that there would be unity among BBIPOC (Black, Brown, and Indigenous People of Color) so that we may glorify God in our pursuit of justice. (Rom. 15:5-7).” Already, we should be nervous about how the Bible is being used in these statements. The verses cited in these prayers refer to the church, not to any ethnic or racial community, which is a mixture of both those within and outside of the people of God.

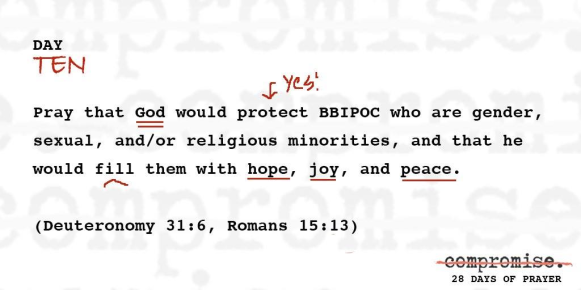

This conflation of the church with the “BBIPOC community” and its intersection with categories of oppression becomes even more prominent in subsequent Tweets. Most notably, on Day 10, we’re asked to “Pray that God would protect BBIPOC who are gender, sexual, and/or religious minorities, and that he would fill them with hope, joy, and peace. (Deut. 31:6, Rom. 15:13)”:

Not only are these verses misapplied to the BBIPOC community, but they are specifically applied to those within that community who are “gender, sexual and/or religious minorities.” Why? The Tweet offers this explanation: “Racism often compounds the adverse experiences of people in vulnerable populations. This week we’re praying for BBIPOC in other marginalized populations.”

While it is right and proper for Christians to pray for marginalized populations, it is improper to apply to them the promises that God has given to the church, to fill us with “hope, joy, and peace as [we] trust in Him … by the power of the Holy Spirit” (Rom. 15:13). Here we see how the “solidarity in oppression” posited by contemporary critical theory has blurred lines between the church and the world, and has prioritized “marginalization” over “redemption” as a fundamental category for solidarity.

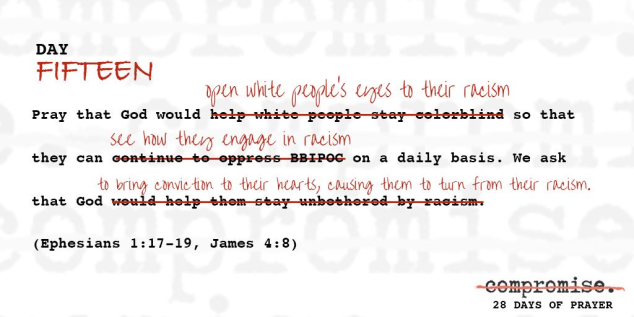

Finally, the epistemology of critical theory is evident in how the #CancelCompromise series positions white Christians with respect to anti-racism efforts. On Day 15, The Witness Tweeted the following image. It reads: “Pray that God would help white people stay colorblind so that they can continue to oppress BBIPOC on a daily basis. We ask that God would help them stay unbothered by racism to [sic] bring conviction to their hearts, causing them to turn from their racism.”

In this image, the struck-through phrases are replaced so that the final tweet reads: “Pray that God would open white people’s eyes to their racism so that they can see how they engage in racism on a daily basis. We ask that God to [sic] bring conviction to their hearts, causing them to turn from their racism” (Eph. 1:17-18, James 4:8). Day 17 continues: “We ask that our white sisters and brothers’ hearts would be turned toward BBIPOC and that the [sic] they would lament their complicity in racism, repent, and repair the damage that racism has caused to BBIPOC.” And Day 18: “We ask that our white sisters and brothers’ hearts would be turned toward BBIPOC and that they would lament their complicity in racism, repent, and repair the damage that racism has caused to BBIPOC.” And Day 19: “We pray once again for our white brothers & sisters in Christ whose hearts are hardened to the truth of racial injustice. We pray that God would soften their hearts. We pray that God would cast down every lie that they believe & replace them w/ the truth.” And Day 21: “We pray that God would bring conviction and repentance to our white brothers & sisters so that they can see the ways in which they are complicit in interpersonal and institutional racism.”

In all these Tweets, we can see the epistemic assumptions of contemporary critical theory at work. Not only is the affirmation that “white brothers and sisters are complicit in racism” taken for granted, it’s also taken for granted that those who deny their complicity are “hardened,” that they believe a “lie,” that they need to have “conviction” brought to their hearts, and that God needs to “open [their] eyes.” The white Christian is therefore placed in a double-bind: he can either admit that he engages in racism on a daily basis, or he can demonstrate that he is racist by denying that he engages in racism on a daily basis. This kind of Kafka-trap, in which a denial of guilt is further evidence of one’s guilt, is prominent in works by critical race theorists like Robin DiAngelo, whose book White Fragility was positively reviewed by The Witness on July 25, 2018.

Tisby on Critical Race Theory

More recently, Tisby spoke directly about critical race theory (CRT), an academic field that applies a critical theoretical approach to race. In particular, he voiced his skepticism that CRT is a real threat: “I think it’s made up and it’s a distraction… the whole thing is based on this idea that Critical Race Theory –or ‘CRT’, for short– has crept into evangelical circles and threatens to undermine the sufficiency of Scripture (11:21) for Christians.” He speaks specifically about SBC Resolution #9 which affirmed that elements of CRT and intersectionality can be useful for Christians while repudiating the worldviews in which these concepts are embedded. Tisby continues: “this is a made-up problem. From what I’ve seen, a group of mostly white, mostly male Christians decided that CRT was becoming a problem in their circles. And they created a sufficient-enough stink in blog posts (13:58), on Twitter, on podcasts and at conferences to make people sit up and listen.”

How does he explain the concerns being raised? He says: “Now here’s what I think the real issue is: white fragility. Yeah? I said it. I think what had happened was some Christians, including myself, started using words associated with the social sciences (15:16) such as ‘white fragility’, ‘white supremacy’, ‘intersectionality’, ‘power’, and other words. So some people heard this and thought ‘the enemy is within the gate. To arms! To arms!’ Speaking for myself, I find these terms helpful (15:29).”

The issue here is not merely that Tisby finds CRT terms helpful. Rather, the issue is that he is attributing the concerns of critics to “white fragility.” It is the “mostly white” and “mostly male” critics’ defensive posture and unwillingness to deal with issues of race that motivates their criticism. Ironically, Tisby has invoked a particularly pernicious CRT concept (“white fragility“) to explain the motivation of critics who raise the concern that pernicious CRT concepts are influencing evangelical thought!

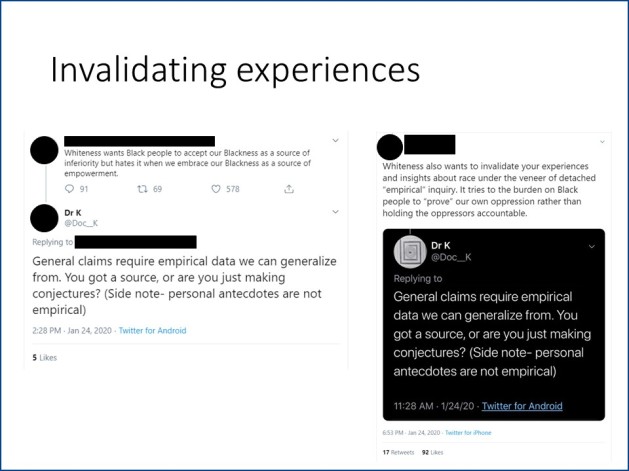

More recently, on Twitter, Tisby claimed that “Whiteness wants Black people to accept our Blackness as a source of inferiority but hates it when we embrace our Blackness as a source of empowerment.” Someone asked him to support his claim with “empirical data we can generalize from.” He responded: “Whiteness also wants to invalidate your experiences and insights about race under the veneer of detached ’empirical’ inquiry. It tries to the burden on Black people to ‘prove’ our own oppression rather than holding the oppressors accountable.”

What’s the relevance?

When I review a book, I’m careful to deal primarily with explicit statements rather than implicit messages or framing. Yet these more subterranean issues can’t be avoided altogether. Understanding the theological and ideological background of an author can help us correctly interpret his meaning. Moreover, in an internet age in which we can place undue weight on spiritual leaders and experts whose pronouncements often go unscrutinzed, it’s often worthwhile to provide readers with gentle cautions. Tisby is highly esteemed for his work on race and Christianity. He routinely speaks at conferences, lectures to large evangelical audiences, and is quoted by prominent pastors. Yet his apparent sympathy for the concepts and framework of critical race theory should give us pause.

On the whole, The Color of Compromise is important and thought-provoking. For the record, I don’t think that questions of reparations or affirmative action are open-and-shut, biblically. These are complex issues, with reasonable arguments available to both sides. Plenty of white Christians do need to think more carefully about the history of racism in the church, their implicit biases, their political commitments, and their willingness to “dialogue across difference” with their brothers and sisters in Christ of other ethnicities. All Christians are called to sacrifice their own preferences and even to lay down their own rights for the good of the body of Christ.

Yet this call goes out to all Christians, not just to those from dominant groups. We’re all commanded to “consider others better than ourselves,” to “be slow to speak and quick to listen,” and to “submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Most importantly, all of our doctrine, beliefs, and practices have to be open to scrutiny. For this reason, embracing a hermeneutic of power which dismisses white, male, Eurocentric voices as blind and irrelevant is exceptionally dangerous. All Christians should be committed to pursuing truth and justice within the bonds of love and peace and under the authority of the Bible. To fail to do so, and to embrace patterns of thought antithetical to Scripture, even for the sake of temporal causes that we deem worthy and righteous, would be compromise indeed.

See all content on critical theory here.

See also my 32-page booklet on “Engaging Critical Theory and the Social Justice Movement”, co-authored with Dr. Pat Sawyer and published by Ratio Christi.

Related articles: