Dr. Eric Mason’s Woke Church is -according to its cover- “an urgent call for Christians in America to confront racism and injustice.”  Coming at a time of increased racial tension and interest in social justice among evangelicals, Dr. Mason’s book attempts to reappropriate the language of ‘wokeness’ for a Christian context. He explores how our understanding of God’s righteousness, the church, and the Christian life should impact our view of race, justice, and ministry.

Coming at a time of increased racial tension and interest in social justice among evangelicals, Dr. Mason’s book attempts to reappropriate the language of ‘wokeness’ for a Christian context. He explores how our understanding of God’s righteousness, the church, and the Christian life should impact our view of race, justice, and ministry.

Pros:

– Dr. Mason’s short book is undeniably rooted in a Christian worldview. When answering the question “What is the gospel?” he quotes 1 Cor. 13:5-6 and Col. 1:21-23 as “truths [that] are central to salvation” (p. 41). He affirms that the church is a family: “Every blood-washed child of God is part of the family of God… As broken as we are, and as separate and splintered and filled with schisms, we are siblings” (p. 60-61). For hope, strength, and power to work for peace and reconciliation, he points to Jesus’ Second Coming: “If the church can keep this image of what is to come to us, we will be energized to work to accomplish His purposes in the earth” (p. 180).

– Dr. Mason recounts the horrors of racism that pervade U.S. history, but adds his personal story, which I found to be moving and persuasive. Because his parents were fifty years old when he was born, they experienced the brutality of Jim Crow first-hand. Dr. Mason’s recounts one of his father’s experiences after being accused of stealing at his workplace: “the police came to my grandfather’s home and snatched my father our of bed. They told my grandmother that if she got in the way, they would kill her… They beat him to force a confession, but to no avail… He was so brutally beaten that [my grandmother] had trouble recognizing him… After hearing the reasoning of my mother’s [white] boss [in defense of Eric’s father], they let him go with no apology or explanation. Some of these men were likely seen as upstanding men in the community, keepers of the law, even leaders in their churches” (p. 76).

– Dr. Mason’s reflection on his father’s story drove home an important point which I’d never really internalized: “These and other experiences colored how I was raised to deal with whites, whether Christian or not. Just as my father’s experiences impacted my perceptions about race, so my perceptions will mark those of my three sons… This is how it works. One generation’s pain and fears are passed on to the next… It doesn’t mean that we must repeat the sins of racism and bigotry of the past, but it does mean that they impact us in some way” (p. 77).

– Finally, the actions steps at the end of the book are good and mostly uncontroversial: “the Imago Dei as Foundational Bible Doctrine” (p. 145), “Listening To and Learning One Another’s Stories” (p. 147), “Enhanced Theological Education” (p. 149), “Facing Our Blind Spots and Apathy” (p. 150), etc… The main exception is his suggestion that we should create programs and ministries that are “unapologetically Christ-driven and unapologetically black, without being seen as separatist” (p 160). Because this statement is likely to generate the most skepticism, it merits some discussion.

– On the one hand, I don’t think that it’s permissible for a church to intentionally divide along racial lines, and I suspect that Dr. Mason would readily agree. Such division would deeply contradict the theology of the New Testament and the example of the early church. On the other hand, understanding the cultural component of the racial divide is important for understanding Dr. Mason’s concerns.

– The Black Church and blacks in the U.S. have a distinctive culture. Of course, blacks aren’t monolithic any more than whites are monolithic, but when blacks enter a predominantly white church, they will likely notice the differences in styles of dress, music, preaching style, service length, order of worship, etc… Given the fact that whites are a numerical majority in the U.S., I think that whites should be especially sensitive not to impose their cultural preferences on blacks. Both blacks and whites need to be willing to make compromises, surrendering their own level of ‘comfort’ for the good of their brothers and sisters in Christ.

– In the same way, we should open to considering ministries geared towards black culture, just as we accept ministries aimed at men and women, immigrants, students, medical professionals, and a variety of other categories.

Cons:

– A few exegetical slips caught my eye, the most significant of which has to do with the following statement: “Man is also reconciled to man by faith. (see 2 Cor. 5:18). God has give us this ministry of reconciliation. He doesn’t give the luxury of refusing to be reconciled” (p. 41). While I agree that reconciliation within the church is a mandate for Christians and is an implication of the gospel, it is not described by this passage. The “ministry of reconciliation” is explained by the next two verses: “We are therefore Christ’s ambassadors, as though God were making his appeal through us. We implore you on Christ’s behalf: Be reconciled to God.” (2 Cor. 5:19-20). These verses speak about reconciliation with God, not reconciliation between humans. While this mistake may seem like a minor point given that the application is true, we have to be careful not to allow our desired application to influence our the interpretation of the text’s meaning. This problem appears to emerge in a much more serious way when it comes to the doctrine of justification.

– Dr. Mason rightly distinguishes between the gospel and the pursuit of justice and repeatedly states that the pursuit of justice is an implication of the gospel. He also clearly lays out the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement in connection to our justification: “God used the injustice of Rome and the Jews as a means for Jesus, the innocent, to take on my guilt and legally pay for my sin (Luke 9:22). He paid for my sin by being my propitiation (1 John 2:2)” (p .44).

– Yet the paragraphs that immediately follow these statements are confusing. Dr. Mason continues “We have to be careful about placing limitations on the attributes of God… Justification is a huge greenhouse of truth that extends beyond ‘being declared righteous’! Justified isn’t merely a position, but a practice!” (p. 45) Given the tremendous significance of the concept of justification (this debate sparked the Reformation!), this statement made me wince. The Reformers diverged from Catholics on precisely this issue: is ‘justification’ a ‘declaration of righteousness’ that is received by faith alone (the Protestant position)? Or does it also include the infusion of spiritual life and the practice of good works (the Catholic position)?

– In the next sentence, Dr. Mason seems to return to the Protestant position: “Christ’s righteousness being imputed to us by faith leads to our being made right with God as well as our making things right on earth” (p. 45).

– Yet the next paragraph begins with the statement: “In essence, we tend to have a one-dimensional understanding of justification. It is important to view the Romans 5-6 and the 2 Cor. 5 sense of righteousness as both intrinsic and extrinsic. In other words, it is an attribute and an action.” (p. 46). These statements seem to veer into a Catholic understanding of justification again.

– Then on the next page, he writes: “Regeneration is a motivation for good works. It is a fruit of gospel transformation… [God’s] philanthropy is both transformative to the soul and expressed by His action upon us. He expect us to be active in good works for His glory as a response and proof that we have been transformed.” (p. 47) These statements are somewhat confusing, but they again seem to lean in the Protestant direction, arguing that good works are the fruit of faith, not a means of justification.

– Why do I raise these points? This entire discussion is found in a section entitled “The Gospel and Justice.” Dr. Mason is quite explicit about his motivation for examining the doctrine of justification: “The way we are taught about these aspects of the gospel [surrounding justification] deeply affects our understanding and the way we process justice. When we have a reductionistic understanding of justification, we fail to see the holistic picture of the gospel.” (p. 46)

– It seems to me that this is an example of how careful we have to be to not let a desired application shape our theology. I understand Dr. Mason’s desire to stir up our passion for justice. Yet achieving this goal by “broadening” our understanding of justification is a dangerous business. By all means, if we have gotten ‘justification’ wrong, let’s pour over the Scriptures and correct our doctrine. But we dare not adjust foundational doctrines for the sake of a desired application, no matter how important the application!

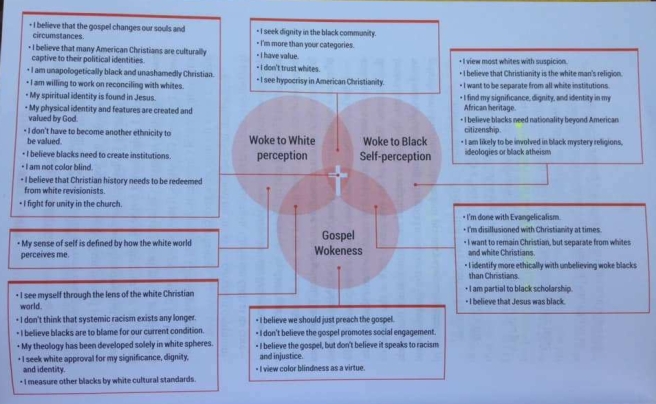

– Lastly, Dr. Mason uses the language of ‘wokeness’ throughout the book. To be ‘woke’ is to be “socially aware of issues that have systemic impact… [it] has to do with seeing all of the issues and being able to connect the cultural, socio-economic, philosophical, historical, and ethical dots” (p. 25). An important ‘wokeness’ Venn diagram is provided on p. 29 (shown below).

– In this diagram, three overlapping circles are labelled “Woke to White Perception”, “Woke to Black Self-perception”, and “Gospel Wokeness.” This diagram draws upon W.E.B. DuBois’ idea of the ‘double consciousness’ of black Americans who “struggle to emerge with a strong sense of self and dignity, while being fully aware of the perception of our people in the eyes of White America” (p. 27). Dr. Mason adds a third category of “gospel consciousness”: “without being conscious in Christ, our souls are still in bondage and can only see things from the natural, fleshly appearance” (p. 27).

– Each region of the diagram is labelled with “general, overarching themes” that are possible within various segments of the black community. The ideal “black Christian consciousness” is found in the center region while the other regions are clearly intended as problematic (they include statements like: “I don’t trust whites”, “I believe that Jesus was black,” “I believe the gospel, but don’t believe it speaks to racism and injustice”, “I’m done with evangelicalism”). However, the ‘bad’ regions in the ‘unwoke’ category are characterized by statements like: “I don’t think systemic racism exists anymore” or “My theology has been developed solely in white spheres” or “I view color-blindness as a virtue.” These statements lead to a serious problem: how should we think about those who disagree with Dr. Mason’s characterization of the ideal ‘black consciousness’?

– For example, well-known black conservatives like Thomas Sowell, Glenn Lowry, or Walter Williams, who have spent decades thinking and writing about race, are certainly “socially aware of issues that have systemic impact.” Yet I’ve never heard anyone classify them as ‘woke.’ We could add black pastors like Voddie Baucham or D.B. Harrison, who are outspokenly opposed to what they view as unbiblical attitudes towards race in the church. If they’re not considered ‘woke’, then the term is is not being used to refer to social awareness of race and injustice. It is instead being used to refer to a particular approach to race and injustice. But how can we be sure that this approach is correct?

– If a black Christian sees color-blindness (as they define it) as the appropriate Christian attitude towards race, has no problem with theology developed solely in white spheres, and denies that ‘systemic racism’ exists today, they are clearly outside of the ‘ideal’ center region of the diagram. But what do we say to them? This issue is, to me, the main problem with the ‘woke’ metaphor: it equates disagreement with blindness. If our racial narrative is built around contrasting our consciousness to others’ obliviousness, it seems difficult to approach the issue objectively and self-critically.

– Of course, this adversarial attitude can be found on both sides: many people shut down dialogue by insisting that those with “progressive” views on race are “Marxists” and “race-baiters.” But the solution is to drop the focus on motives and lived experience, and to instead turn our focus to Scripture, reason, and brotherly dialogue. We all have blind-spots and we all need our brothers and sisters in Christ to help us see them.

Summary:

Woke Church provides a good introduction to the ‘woke’ movement among evangelicals, both its positives and its pitfalls. It offers numerous suggestions that all Christians should be able to support, regardless of where they stand on the social justice debate. And it offers personal perspectives that help the reader understand how a black evangelical experiences the evangelical movement in the 21st century. At one point, Dr. Mason admits that “As much as I may want to give up on evangelicalism, I cannot give up on Jesus and the church” (p. 61). I pray that he remains true to this admirable commitment to his evangelical brothers and sisters in Christ.

Related articles:

- Blind But Now I See – A Review of Daniel Hill’s White Awake

- Reconstructing the Gospel or Obscuring It? A Review of Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove’s Reconstructing the Gospel

- Should We “De-colonize our Theology”?