Do we want to be loving? Or do we want to be perceived as loving? When our beliefs about what is right force us to push against the culture, what will we do? Will we follow the evidence and consider alternative hypotheses even if we see them heading in an unpopular direction?

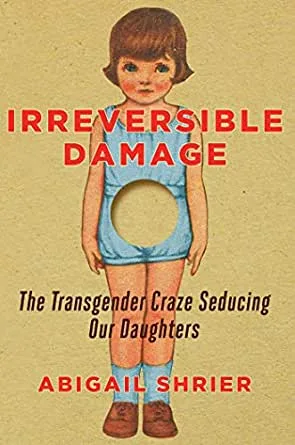

These questions should haunt anyone who reads Abigail Shrier’s Irreversible Damage and encounters story after story of troubled teenage girls who embrace transgender ideology, pursing a course of social transitioning, hormone therapy, and even surgery. Many of these narratives follow a similar pattern: a normal girlhood with little discomfort, an awkward adolescence, difficulty making friends, the discovery of the online trans community, the announcement of a non-binary gender identity, increasing mental health problems, anger and misery, collapsing grades, and alienation from family. Some of the stories lead to total estrangement; others have happier endings. But all of them embody a parent’s worst nightmare: a child falling deeper and deeper into chaos in spite of the desperate efforts of her family.

The Onset

The typical response to these stories is to suggest that the child lacked affirmation and a supportive environment. Yet the parents interviewed by Shrier make it difficult to sustain this claim. The majority of them were progressives who went along with the affirmation-only mandate of therapists and medical professionals. One set of parents was a lesbian couple. Another mom was a leader in PFLAG (the “first and largest organization for… LGBTQ+ people” according to their website). None of them seem to have had moral or religious objections to transgender and Shrier repeatedly states that she has no objections to adults transitioning. What Shrier and all of these parents have in common is a concern over the way in which gender transition in children is being affirmed, normalized, and lionized within our culture. We’re told that teenagers, elementary schoolers and even kindergarteners just know they are trans. But are we sure that’s the whole story?

One of the researchers who openly questions this claim is Dr. Lisa Littman, whose peer-reviewed PLoS One article on “rapid-onset gender dysphoria” (ROGD) created tremendous controversy when it was first published in 2018. Dr. Littman was trying to understand why countries “across the Western world… were reporting a sudden spike in gender dysphoria–the medical condition associated with the social designation ‘transgender.’ Between 2016 and 2017 the number of gender surgeries for natal females in the U.S. quadrupled… In 2018, the UK reported a 4,400 percent rise over the previous decade in teenage gender treatments” (p. 25-26). Dr. Littman investigated this phenomenon by interviewing hundreds of parents, 85 percent of whom “identified as supporting LGBTQ rights” (p. 28). Shrier writes:

Two patterns stood out: First, the clear majority (65 percent) of the adolescent girls who had discovered transgender identity in adolescence –“out of the blue”– had done so after a period of prolonged social media immersion. Second, the prevalence of transgender identification within some of the girls’ friend groups was more than seventy times the expected rate…The atypical nature of this dysphoria–occurring in adolescents with no childhood history of it–nudged Dr. Littman towards a hypothesis everyone else had overlooked: peer contagion. (p. 26-27)

In other words, Dr. Littman suggested that at least some of these girls were caught up in what amounts to a cultural fad, albeit one with far more serious implications than Justin Bieber or Pokemon. But is there any reason to think that there might be cultural pressures pushing adolescents towards transgender identification? Answering that question requires us to dive deeper into the worlds of YouTube influencers, therapists, and school administrators, all of whom –Shrier argues– are contributing in various ways to the transgender phenomenon.

The Cultural Current

“I want you to know that it’s okay to walk away from unsupportive or disrespectful or even abusive parents…I want to give you hope that you can find what we call your ‘glitter family,’ your ‘queer family.’ We are out there, and the relationships that we make in our glitter families are just as real, just as meaningful as our blood families” (p. 51).

These are the chilling words of 35-year-old transgender cyclist Rachel McKinnon from a YouTube video posted on Mother’s Day 2017. In her research, Shrier discovered an entire online community dedicated to encouraging, instructing, and guiding youth who are exploring whether they are transgender. She lists several mantras she heard repeated by numerous popular figures:

- “If you think you might be trans, you are.” (p. 44)

- “Trying out trans? [Breast] Binders are a great way to start.” (p. 46)

- “Testosterone, or ‘T,’ is amazing. It may just solve all of your problems.” (p. 48)

- “If your parents loved you, they would support your trans identity.” (p. 49)

- “If you’re not supported in your trans identity, you’ll probably kill yourself.” (p. 51)

- “Deceiving parents and doctors is justified if it helps transition” (p. 52)

- “You don’t have to identify as the opposite sex to be ‘trans'” (p. 53)

Videos making theses claims have tens of millions of views and trans personalities like Chase Ross and Ty Turner have hundreds of thousands of followers. Teenagers questioning their gender can quickly be sucked down an algorithm-generated rabbit hole into a Wonderland populated by colorful, charismatic stars all echoing the joys of finding their “true selves.” Yet some of this advice should strike parents as eerie if not outright alarming. Should YouTube personalities with no medical training be extolling the virtues of a Schedule III drug like testosterone or telling kids that if their parents don’t unequivocally support their identity, they’ll be driven to suicide?

Other social factors may also play a role in the transgender phenomenon. In Dr. Littman’s paper, over 90 percent of the girls who experience rapid-onset gender dysphoria were white. Within an intersectional framework, they therefore find themselves among a dominant, oppressor group which, ironically, puts them at a social disadvantage. “What to do about it?” Shrier asks. “They can’t choose to be people of color. Most can’t choose to be gay. Nor can they choose to be disabled” (p. 154). Prof. Heather Heying suggests that trans identity is the only viable way for these girls to attain victim status: “‘All you have to do is declare ‘I’m trans’ and boom, you’re trans. And there you get to rise in the progressive stack and you have more credibility in this intersectional worldview‘” (p. 155). If we’re skeptical that people would chose to identify with a marginalized group merely to boost their social status, recent stories of white adults pretending to be Black demonstrate that this phenomenon is by no means limited to teenagers.

Yet the internet and their peer group are not the only places where trans-identifying youth can find unreserved affirmation. Both are increasingly present within the education and medical communities.

The Adults in the Room

Anyone who has raised (or has been) a teenager knows that they can be emotional, impulsive, and careless. For that reason, both legally and practically, we limit their agency and set boundaries. Unfortunately, with regard to the subject of gender identity, we seem to have abandoned these guardrails.

For example, schools often have explicit policies in place that affirm a student’s gender identity without the parents’ consent or even knowledge. Gender and sex education starts as early as kindergarten. In 2019, California drafted a health education framework for grades K-3 which stated that “some children in kindergarten and even younger have identified as transgender or understand they have a gender identity that is different from their sex assigned at birth.” C. Scott Miller, a 5th grade public school teacher and liaison to the California Teachers Association, explained why children are not necessarily encouraged to share their gender identity with parents: “As much as parents want to have rights, what they need to do is be involved in the process… It’s not the school’s obligation to call up and ‘out’ a kid to a parent because you’re not sending that kid home to the gay pride parade. You’re sending them home to somewhere that’s going to be very unsafe and a lot of misinformation, a lot of anger and it’s just not going to be a safe place for that kid” (p. 67). Elsewhere, he was even more blunt: “Even parents that come in and say, ‘I don’t want my kid to be called that.’ That’s nice, but their parental right ended when those children were enrolled in public school” (p. 75).

Therapists and medical professionals have also embraced the idea that they must not in any way challenge their patients’ beliefs or desires with respect to their gender identity, even when that patient is a child. The standard of affirmative case “asks –against much evidence, and sometimes contrary to their beliefs on the matter– that mental health professionals ‘affirm’ not only the patient’s self-diagnosis of dysphoria but also the accuracy of the patients’ perception… Affirmative care compels therapists to endorse a falsehood: not that a teenage girl feels more comfortable presenting as a boy–but that she actually is a boy” (p. 97-98). This standard has been adopted by “the American Medical Association, the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Psychological Association, and the Pediatric Endocrine Society” who have all “endorsed ‘gender-affirming care’ as the standard for treating patients who self-identify as ‘transgender’ or self-diagnose as ‘gender dysphoric'” (p. 98).

Dr. Ray Blanchard, who was the head of Clinical Sexology Services at the Toronto Centre for Addiction and Mental Health finds this position to be inappropriate: “I can’t think of any branch of medicine outside of cosmetic surgery where the patient makes the diagnosis and prescribes the treatment. This doesn’t exist. The doctor makes the diagnosis, the doctor prescribes the treatment. Somehow, by some word magic or word trickery, gender [activists] have somehow made this a political issue” (p. 131).

Shrier concurs: “Imagine we treated anorexics this way. Imagine a girl –5’6” tall, 95 pounds– approaches her therapist and says: ‘I just know I’m fat. Please call me “Fatty.”‘ Imagine the APA encouraged its doctors to ‘modify their understanding’ of what constitutes ‘fat’ to include this emaciated girl. Imagine the APA encouraged therapists to respond to such patients, ‘If you feel fat, then you are. I support your lived experience. Okay, Fatty?'” (p. 99). We would react with horror. Yet we’ve chosen not only to adopt this approach but to forbid, sometimes to legally forbid, all others. This is madness. To warn a teenager or a pre-pubescent child against making permanent, life-altering decisions based on nothing more than their self-perception is not paternalism; it’s our duty as adults. But it’s a duty we’ve apparently chosen to ignore.

The Silencing

As troubling as these policies are, perhaps more troubling is the way in which any dissent or skepticism has been consistently silenced. In case after case, anyone who has objected to gender orthodoxy have been vilified, harassed, or fired. Dr. Littman, whose paper on ROGD “drew praise from some of the most distinguished world experts on gender dysphoria” (p. 29) was denounced as a bigot. Brown University retracted their press release on her paper and PLoS One issued an apology. Activists convinced the Rhode Island Department of Health to terminate her consultancy.

Dr. Kenneth Zucker, who helped write the entry on “gender dysphoria” for the DSM-5 and the “Standards of Care” for the World Professional Association for Transgender Health was fired from his job and had his clinic closed, despite the fact that “five hundred mental health professionals from around the world signed an open letter to [Toronto’s Center for Addiction and Mental Health] protesting his firing” (p. 126).

When openly lesbian tennis legend Martina Navratilova penned an article for the Sunday Times stating that it would be unfair to let biologically male athletes compete against biological women, she was –unsurprisingly– labeled a bigot and a transphobe. Her sponsor, Athlete Ally, dropped her, saying “The trans community is under attack and we firmly stand opposed to any and all people who perpetuate attacks against them” (p. 152).

Shrier herself has faced various forms of pressure and deplatforming in her attempt even to get Irreversible Damage published. Amazon would not allow her publisher to run ads for the book. In response to an angry Tweet, Target decided to pull the book from its shelves before backtracking. Spotify employees threatened to strike over Shrier’s interview with podcaster Joe Rogan.

At every turn, anyone who challenges gender orthodoxy is reviled as a bigot. Is that reasonable? Shouldn’t it be troubling to us that even world-renowned scientists who have been treating transgender patients for decades are being fired and silenced the minute they challenge the official narrative? With so few good studies to guide us on the long-term effects of a cultural development that’s no more than 10 years old, can we afford to shout down all debate?

The Alternative

At this point, progressives may begin feeling uncomfortable. Everything in our culture, all of the approved people, are presenting us with a vision, a moral vision, of tolerance and love and acceptance and affirmation. But real love is always rooted in truth. Young girls and boys are taking powerful drugs that will render them sterile and are cutting off their genitals in the hopes that it will solve their problems. Think past the airbrushed world of VH1 trans models. This is not a harmless experiment.

After discussing the risks and difficulties of various surgeries and medical treatments, Shrier writes:

The dangers are legion. The safeguards absent. Perhaps the greatest risk of all for the adolescent girl who grasps at this identity out of the blue, like it is the inflatable ring she hopes will save her, is also in some ways the most devastating: that she’ll wake up one morning with no breasts and no uterus and think, I was only sixteen at the time. A kid. Why didn’t anyone stop me? (p. 183)

This question should stop us dead in our tracks. Of course, there are those who genuinely hate transgender people. But there are others who know and love transgender people, who want what is best for them, and who truly believe that gender transition is not the way. Hopefully, Irreversible Damage will lead people to question the dictates of woke orthodoxy so that these topics can be discussed openly. For most people, saying that “compassion” requires us to encourage a troubled 16-year-old girl to cut off her breasts is a bridge too far. If we let our fear of public disapproval weigh more heavily on us than the actual good of our neighbor, then we’re not loving them; we’re merely using them to bask in the glow of our own self-righteousness. May that not be the case.

See all content on critical theory here.

Related articles: