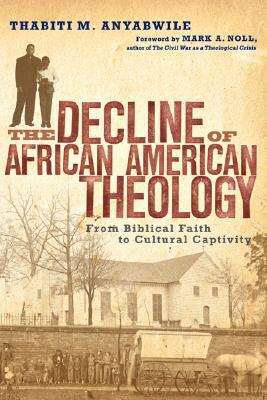

Thabiti Anyabwile’s The Decline of African American Theology: From Biblical Faith to Cultural Captivity is a work of historical theology that traces the dominant doctrinal beliefs of Black Americans from the period of slavery, through Reconstruction, and the Civil Right’s Movement, to the 21st century.  Anyabwile’s main thesis is that the “clarity of early theological insight” among black Christians produced “perhaps the most authentic expression of Christianity in American history, forming the basis for the African American church’s engagement in both the propagation of the gospel and social justice activism” (p. 17). But this “theological basis for the church’s activist character was gradually lost and replaced with a secular foundation” as the church became “less critical theologically and increasingly more concerned with social, political and educational agendas… As a consequence of theological drift and erosion, the black church now stands in danger of losing its relevance and power to effectively address the spiritual needs of its communicants and the social and political aspirations of its community” (p. 18).

Anyabwile’s main thesis is that the “clarity of early theological insight” among black Christians produced “perhaps the most authentic expression of Christianity in American history, forming the basis for the African American church’s engagement in both the propagation of the gospel and social justice activism” (p. 17). But this “theological basis for the church’s activist character was gradually lost and replaced with a secular foundation” as the church became “less critical theologically and increasingly more concerned with social, political and educational agendas… As a consequence of theological drift and erosion, the black church now stands in danger of losing its relevance and power to effectively address the spiritual needs of its communicants and the social and political aspirations of its community” (p. 18).

Anyabwile divides the history of African American theology into five periods: “Early Slavery Era Through Abolition,” “Reconstruction [through] the ‘New Negro’ Movement,” “Depression and WWII,” “Civil Rights Era,” and the “Postmodern Era” (p. 19). As a work focused on theology, each chapter focuses on a different core doctrine: Revelation (Chapter 1), God (Chapter 2), Anthropology (Chapter 3), Christology (Chapter 4), Soteriology (Chapter 5), and Pneumatology (Chapter 6). While I don’t have the background to offer an independent historical analysis of Anyabwile’s claims, they seem to be well-documented. Consequently, I’ll confine myself to my own impression of the book.

First, I was struck by the testimony of slaves’ love for the Bible: “slaves recognized that learning to read the Bible… was real spiritual power… So, slaves vowed to learn to read before they died so that they could read the Bible… often risking legally sanctioned retribution, severe beatings and death” (p. 37). Conversely, I was struck by the extreme wickedness of slave-holders who deliberately prevented their slaves from learning to read or from having access to the Bible. For example, slave John Jea wrote:

Such was my desire was being instructed in the way of salvation, that I wept at all times I possibly could, to hear the word of God, and seek instruction for my soul; while my master still continued to flog me, hoping to deter my from going, but all to no purpose, for I was determined, by the grace of God, to seek the Lord with all my heart, and with all my mind, and with all my strength, in spirit and in truth, as you read in the Holy Bible (p. 37)

This reverence for Scripture and reliance on it as the sufficient revelation of God, even in the face of resistance and brutality, was echoed by writers like Jupiter Hammond (p. 27-28) and Daniel Payne (p. 28-31).

I was also moved at many times by quotes from early Black authors throughout the book expounding on doctrines like the sovereignty of God, the nature of Christ, or the atonement. I was reminded of the great truth that biblical doctrine unites Christians as brothers and sisters in Christ across time and space. Love for a common savior breaks down the barriers that the world and sin erect.

Several historical figures serve as theological touchstones in the book, including Hammond, Payne, Lemuel Haynes, Marcus Garvey, Howard Thurman, T.D. Jakes, and Creflo Dollar. But Anyabwile’s lengthiest treatment (and most stinging denunciation) is reserved for James Cone, founder of Black Liberation Theology. Cone believed that the Bible should be read through the lens of the black freedom struggle and that all theology should be evaluated in terms of its promotion of black liberation. Because God identifies with the poor and oppressed, he believed that it’s legitimate to characterize God as “black.”

Summing up his argument against Cone’s theology, Anyabwile writes:

God does not exist…to affirm the ethnic identity and self-worth of any single people. Nor does God so identify with a people, even in his sovereignly elected people Israel or the church, to the point that he becomes one with that people without regard for their holiness and proper worship…The history of African American Christology is partly a history of selective Bible reading. The Christ that appears in the writings of many is an idol of their own making, a god graven with the tools of self-esteem and self-advancement… Jesus never acted in a way that suggested a political liberation for his contemporaries – to the consternation and disappointment of many would-be followers of his time and ours (Jn. 6:14-71)… He did not come to ‘set the captives free’ in any political or military sense…To the extent that African American thinkers obfuscated the centrality of Jesus’ spiritual mission to purchase a special people for himself, they traded their heavenly birthright for a mess of socioeconomic pottage. This is no victimless crime. Materialism and black nationalism masquerading as Christology overthrow the faith of many – shrouding the cross of Jesus in the temporal affairs of this world, which in turn choke the seeds of the gospel. p. 170-171

Anyabwile also cautions against allowing temporal or political concerns to supplant the primacy of the preaching of the gospel. He affirms that “[t]here is a place in Christian theology… for radical jeremiads against bigotry, injustice and oppression of all kinds” (p. 171). However, he warns that:

the [black] church is largely viewed as irrelevant by vast numbers of mostly young African Americans, despite concerted efforts to make the church a multipurpose human services organization with housing, child care, after school, health care, economic development and other social service programs. It seems the more the church does the less relevant it becomes. The reason for this state of affairs is that the unbelieving world tacitly understands that the primary reason for the church’s existence is not temporal. Though the world is wracked with pain and suffering, it intuitively grasps the fact that the answers it longs for are transcendent, not earthly. So, the more the church appeals to the world’s felt needs and physical deprivations, the more irrelevant it becomes to those who lack a true and saving knowledge of Jesus Christ. The church needs to be revitalized with a sound theology and a praxis governed by the Word of God. (p. 245)

Anyabwile’s prescription for this mission-drift is found in the book’s closing section under the heading “Recover the Gospel”:

We must return to making the biblical gospel the foundation for our Christian fellowship and our social ethics. That gospel holds that man is ruined in sin, estranged from God and in profound danger of eternal torment and condemnation in hell. But, God, who made man in his own image for eternal fellowship with him, has acted in history to redeem man from sin and his wrath to come. God the Father sent God the Son to live the perfect life of worship and obedience to God that we could not and would not live. Jesus volunteered to both live that life and to pay the penalty of death that we owed for our sin. He suffered on Calvary’s cross, died a criminal’s death as a substitutionary propitiation and atonement for our sins. Three days later, he was raised from the dead victorious over sin, death and the grave. Now, all who repent of their sin and believe on Jesus will be saved from the just penalty of their sins, justified before God and given a new life with God. This is the message of Christianity, the message that should dominate all Christian preaching. (p. 244)

As someone with no background in history, I’ll offer only a two mild criticisms of the book. First, I was surprised that Martin Luther King, Jr. did not feature more prominently, given how large his figure looms in American history. It would have been helpful to position him theologically in relation to Hammond and Payne on the one hand, and Garvey and Cone on the other.

More importantly, I think the book should have emphasized that the “decline of African American theology” is exactly mirrored, and perhaps surpassed, by the overall decline of American theology. Anyabwile mentions on p. 18 that the secularism overtook the Black church “along with its ‘white’ counterpart,” but this this point was largely underdeveloped. I wouldn’t want readers to walk away with the impression that the historic Black church is an outlier with respect to the incursion of liberalism. The loss of doctrines like the authority of Scripture, the sovereignty of God, the depravity of man, and the deity of Christ are by no means unique to African American theology.

In summary, Anyabwile’s book is an excellent, even-handed treatment of a sensitive topic. His emphasis on Reformed theology and his assertion of the primacy of the preaching of the gospel to the mission of the church are wake-up calls that are desperately needed today.

Related articles: