Yesterday, Ameen Hudson wrote an important article at The Witness on “Biblical Justice and The Specter of Cultural Marxism.”

I agree with every single word of it.

Will this be the shortest response in the history of the Internet? Not quite.

In the spirit of dialogue in which I believe the article was written, I’d like to gently raise some concerns – not with what the article included but with what it left out. Before I do that, though, let me give the article the praise it deserves.

Getting things right

First, Hudson is right to point out that -all too often- people use the label ‘cultural Marxism’ to dismiss ideas out of hand without engaging them rationally or charitably. I have been making exactly the same point in all my recent talks and articles. Fellow conservatives, don’t be this guy:

Hudson draws an excellent analogy to the use of words like ‘bigot’ or ‘racist’, pejorative labels which substitute for actual arguments. The Golden Rule of discourse is the Golden Rule itself: if you don’t want other people misrepresenting your ideas and lobbing labels at you, apply the same standards to your own tactics.

If this ethical argument is insufficient, let me offer a purely pragmatic one: calling people names will not open them up to dialogue. If you want to reach someone, treat them kindly. If an idea is false, it’s false no matter what we call it. Focus on arguments and evidence, not labels.

Second, Hudson is right that not all ‘cultural Marxists’ are equal (see what I did there?) The term is nebulous. What exactly is ‘a cultural Marxist’? What do they believe? If we can’t point to a body of academic literature, or a set of books, or a set of shared ideas with which the majority of ‘cultural Marxists’ would agree, then it’s not a particularly useful term.

Let me also offer another practical problem: if the term ‘cultural Marxist’ isn’t well-defined, then it’s easy to avoid. For example, Hudson points out that many Christians who are concerned with racial equality want to ensure equality of opportunity, not equality of outcome. Because Marxism is concerned with equality of outcome, he argues that the charge of ‘cultural Marxism’ is specious when applied to his own beliefs. Case closed.

Finally, in what is undoubtedly one of the more inflammatory comments in the post, Hudson charges that “many Christians don’t fight against injustice because they simply don’t care.” I’ll say more about this statement below, but let’s parse it carefully. Strictly speaking, is it true or false? It’s true. In a nation of over 300 million people, 75% of whom identify as Christian, you don’t think there are ‘many’ who simply don’t care? As people who are Simul Justus et Peccator (at once righteous and sinner), let’s search our hearts before we write this claim off as mud-slinging.

With all these points of agreement, with what did I disagree? Read on.

A rose by any other name

While I avoid the term ‘cultural Marxism’ entirely, it is attempting to describe a real ideology, known as critical theory. Critical theory does see the world as a battleground between oppressed groups and their oppressors and sees our primary moral duty as liberating groups from oppression.

I’ve written extensively on critical theory elsewhere, but for now, I merely want to point out that it isn’t a shadowy conspiracy theory that involves the Illuminati, Lizard People, and copious amounts of tinfoil. Instead, critical theory forms the basis for numerous academic disciplines such as critical pedagogy, critical race theory, gender studies, and queer theory.

Given the fact that many of the foundational premises of critical theory are antithetical to Christianity, Christians should be worried about its growing influence in our culture, in the social justice movement, and even in the church. Hudson should acknowledge the legitimacy of this concern, even if he rejects the label of ‘cultural Marxism.’ In the next section, I’ll give just one example of how the basic axioms of critical theory lead to a slippery slope that undermines traditional Christian beliefs.

Opportunity to what?

Critical theory affirms that our fundamental moral duty is to liberate groups from oppression so that a state of equality can be achieved. But what exactly would happen if a Christian enthusiastically embraced the idea that “we should tear down all systemic and institutional structures that prevent equality” and then followed that idea to its logical conclusion?

Could they continue to maintain that the opportunity to be an elder should be limited to men only? Could they continue to believe that only men should have the opportunity to lead their family spiritually? Could they continue to insist that only heterosexual couples have the opportunity to marry? Could they continue to insist that Christian student groups should be able to deny leadership roles to non-Christians?

It turns out that this issue is complicated. Justice is not identical to “liberating groups from oppression,” at least as ‘oppression’ is understood by critical theory. Yet some evangelicals, influenced by the premises of critical theory, assume that it is. The trajectory towards theological liberalism that such figures have followed in recent years is not a random, undirected drift. It is a steady outworking of their belief that “we should tear down all structures that prevent equality.”

I’m extremely glad that Hudson holds the traditional view on all these issues. But the same could have been said of other evangelicals, who nonetheless found their views evolving as their commitment to the presuppositions of critical theory supplanted their commitment to biblical doctrine.

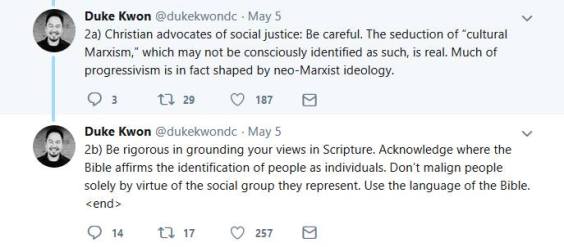

As fellow Witness author Duke Kwon wisely writes: “Christian advocates of social justice: Be careful. The seduction of ‘cultural Marxism,’ which may not be consciously identified as such, is real. Much of progressivism is in fact shaped by neo-Marxist ideology…Be rigorous in grounding your views in Scripture. Acknowledge where the Bible affirms the identification of people as individuals. Don’t malign people solely by virtue of the social group they represent. Use the language of the Bible.”

While there are people who are using the term ‘cultural Marxism’ dismissively to shut down dialogue and end engagement, there are others (like me) who are trying to call attention to what we think is a very serious issue, out of love for our brothers and sisters in Christ.

Equal weights and measures

Finally, Hudson emphasizes that we need to hold to nuanced and charitable positions, especially with respect to other believers. I fully agree. Is he consistent here? I’m not sure. For example, imagine I copied the following paragraph from Hudson’s essay, but modified it slightly:

I believe many Christians embrace unbiblical conceptions of justice because they simply don’t care about the Bible. Their hearts are not as moved as they should be by the authority of Scripture which has its own set of fearful implications. But I think some also fear they’ll align themselves with the specter of conservatism or fundamentalism. It’s what cultural commentators have told them, and they’ve come to believe it. This sadly prevents them from honest self-examination and humble listening.

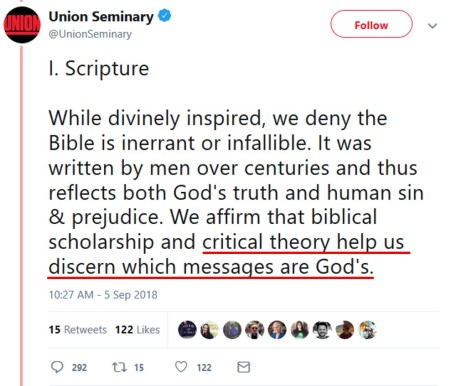

Now, strictly speaking, is this true or false? Is this an accurate description of ‘many’ Christians in a nation of 300 million people? Certainly. Just consider this tweet from Union Theological Seminary:

Some Christians aren’t making any attempt to reform their beliefs to Scripture, but are instead letting their cultural values override the Bible. But while my statement is strictly true, does it convey exactly the kind of uncharitable impression that Hudson warns against? I think so.

Hudson doesn’t mention the other half of the picture. Yes, there are ‘many’ Christians who don’t care about justice. But there are also ‘many’ Christians who embrace unbiblical ideas of justice to keep in lockstep with progressivism. We can silence people and shut down dialogue by writing them off as ‘cultural Marxists’ who are motivated by political correctness. But we can also silence people and shut down dialogue by writing them off as fundamentalists who are motivated by indifference to justice. Biblical balance seeks to illuminate and avoids both errors.

In conclusion, I fully agree with Hudson that we need to truly understand and correctly represent people’s positions before challenging them. Moreover, let’s assume the best of the motives of other believers, even when we believe that they are seriously mistaken. In all these discussions, we should extend grace and charity to our brothers and sisters, listening well to one another and to Scripture for the glory of God.

Related articles:

- Critical Theory and Christianity (article)

- Critical Theory – All Content

- Christianity and Critical Theory (talk)

- A Long Review of Race, Class, and Gender