Megan Basham’s Shepherds For Sale is a blistering indictment of evangelical leaders who, in the words of Basham’s subtitle, “Traded the Truth For a Leftist Agenda.” The book sparked heated controversy on social media, quickly dividing evangelicals into pro- and anti-Basham factions. Basham seems to have anticipated this reaction, concluding her book with the following admonition:

No one, least of all Christians, should welcome civil war in the Church. But too many Church leaders have grown arrogant due to the rank and file’s reluctance to seem unpleasant or uncharitable by confronting their deceit and manipulation… Open war is upon us and has been for a number of years… The time has come to pick up [the sword of Scripture] and unashamedly use it against the cunning and craftiness of people who would see us blown here and there by every wind of teaching (p. 242-243)

Basham is not merely opposing generic progressive drift within evangelicalism. Rather, she names names, calling out high-profile leaders and pastors and categorizing them as “Wolves, Cowards, Mercenaries, and Fools” (p. xxi).

For many critics of the book, it is a work of false, divisive, and dangerous propaganda that should be dismissed out of hand. For many of its fans, it is a shocking, immaculately researched, courageous exposé on thorough-going evangelical compromise. In this review, I’ll argue that neither assessment is entirely correct.

Full disclosure: J.D. Greear is one of the book’s main targets and has been my pastor for 14 years. I know him personally and consider him a friend. I acknowledge the conflict of interest that this relationship entails. For that reason, I will mention him only occasionally in this review. Nonetheless, I have tried to remain as objective as possible and will try to treat this book the way I’d treat any other book I review. More importantly, I urge readers to evaluate the arguments I make. The accusation “You only say that because J.D. is your pastor” is just as irrelevant to the validity of my claims as the accusation “You only say that because you’re a straight White male.” Claims are true or false independent of who makes them.

External pressure

Prior to reading Shepherds for Sale, I would have been skeptical about the extent to which progressive groups were trying to influence evangelical attitudes. I would have been wrong. Basham repeatedly documents ways that progressive activists and grant agencies have overtly tried to shape the very sizeable and reliably conservative evangelical voting bloc to promote their own views.

For example, the progressive group New America published a report in 2015 explaining the strategy of the Evangelical Environmental Network:

EEN leaders hoped to win the ERLC’s support for Creation Care, because even just neutralizing the Southern Baptist Convention in the debate on global warning could disrupt the solid Republican opposition to measures like cap and trade. (p. 7)

Similarly, in a document entitled “Supporting Safety and Progressive Faith Voices to Secure LGBTQ Social Justice” the progressive Arcus Foundation says it’s committed to “Increasing the visibility and influence of affirming faith leaders” and to “challenging the promotion of narrow or hateful interpretations of religious doctrine” (p. 203, c.f. Ref 13).

Basham likewise calls attention to how progressive groups have funded or awarded grants to evangelical organizations like the ERLC (p. xxi), the Evangelical Immigration Table (p. 42-43), and Christianity Today (p. 74).

Even the staunchest of Basham’s critics should acknowledge the validity of her concerns here: evangelical organizations that receive funds from external sources need to be exceptionally cautious about the subtle or explicit pressure that these connections can exert.

The progressive gaze

A second positive element of Basham’s book is her recognition that the desire for approval is extremely powerful. Indeed, to some extent, her title “Shepherds for Sale” obscures the important role of social factors in leftward drift: “Institutional prestige, seeing oneself lauded on CNN and in the Washington Post as more intellectually and morally advanced than the rest of the evangelical rabble can also be a potent elixir” (p. xxii).

Mark Galli, the former editor-in-chief of Christianity Today, admitted to exactly this dynamic in a blog post, where he wrote:

For the longest time, a thrill went through the office when Christianity Today or evangelicalism in general was mentioned in a positive vein by The New York Times or The Atlantic or other such leading, mainstream publications. The feeling in the air was, ‘We made it. We’re respected’… (p. 76)

He goes on to openly admit that this “hunger for worldly respectability” drove the magazine’s editorial coverage (p. 77).

Another factor in evangelical compromise stems from a largely positive motive: evangelism. Evangelicals in highly progressive areas want their neighbors to repent and believe the gospel. They see “conservative politics” as an obstacle to their neighbors’ conversion and therefore either mute or downplay their own political beliefs.

However, the chasm between conservative and progressive politics in 2024 is not the result of purely political issues like the marginal tax rate or the wisdom of trade tariffs. Rather, it is the result of fundamentally theological questions like: “what is a human being?” “Should there be any constraints on our autonomy?” “What is the basis of law?” If we conceal our actual beliefs about these issues for the sake of bringing non-Christians to church, we are operating more like a cult than like Christians.

Critics like Basham are also correct to see an asymmetry in how we treat different political factions, as summarized by the pithy phrase: “punch right, coddle left.” That is, when we speak about abortion or homosexuality, sins ignored by the Left, we speak with gentleness and nuance — if we speak at all. But when was the last time we spoke with gentleness and nuance about racism? Yes, if ours is the only evangelical church in the heart of a deep-blue urban center, we may have to spend a fair bit of time deprogramming guests’ false stereotypes about evangelicals. But we cannot preach a message that never challenges, and constantly panders to, progressive sensibilities.

#BigEva Delenda Est

Finally, Basham’s book has been so successful in part because it has tapped into a groundswell of opposition to #BigEva, the loose collection of evangelical parachurch organizations, conferences, and publishers that dominate institutional evangelicalism. #BigEva includes organizations like The Gospel Coalition, Christianity Today, Acts 29, CRU, and World Relief, all of which are named in the book.

Judging from social media, the prevailing sentiment among “evangelical dissidents” is that #BigEva is filled with regime theologians who are -at best- useful idiots and -at worst- quislings. They constantly repeat leftist propaganda and sneer at everyday evangelicals. They crave respectability and gatekeep unapproved voices to deprive the unwashed masses of a platform. When they are caught in an error, they circle the wagons and refuse to admit their mistakes.

These complaints suffuse the book, but are best captured by the ironic title of Chapter 5: “Gracious Dialogue: How the Government Used Pastors to Spread Covid-19 Propaganda.” In that chapter, Basham argues that prominent evangelicals consistently parroted government talking points about the origin of COVID, the utility of masks, the efficacy of vaccines, and the importance of school shut-downs and church closures.

She raises similar concerns elsewhere. At the end of Chapter 1 on climate change, she writes: “These are complex topics. It is not wrong for pastors and Christian leaders to weigh them and debate them. But it is wrong for them to make agreement on environmental politics a test of biblical faithfulness [or to] bind consciences with a blithe and unthinking ‘Love your neighbor.’” (p. 30). And, on illegal immigration, “To insist that [the command to ‘welcome the stranger’] was meant to be used as a blanket immigration policy is spiritual manipulation that cheapens its meaning. And to insist that pastors should use their pulpits to shame congregants into becoming activists for debatable legislation cheapens the mission of the Church” (p. 50).

Note that in all these cases, Basham is not decrying the fact that Christian leaders are personally taking a certain position, but that they are simplifying it, failing to present both sides, and positioning it as the only intelligent Christian view while simultaneously suppressing dissent.

Another way of framing this discussion is in terms of representation. A growing number of evangelicals feel that their own views are not being represented by evangelical institutions and leaders. For example, we’re frequently reminded that 80% of White evangelicals voted for Donald Trump. But did 80% of articles at Christianity Today or The Gospel Coalition reflect this population? Did they even show that these outlets were sympathetic to the concerns of Trump voters? Of course, Christian leaders do not exist to merely parrot back the popular consensus. However, when it comes to contentious issues, surely large platforms can at least acknowledge that other perspectives exist and can allow the average Christian to feel that his beliefs are taken seriously rather than simply being scoffed at.

Much more could be said about the appeal of this book and about what it gets right. For example, I obviously share Basham’s concern that ideologies like critical race theory and queer theory are making inroads into evangelicalism, having co-authored a 500-page book on this subject with Dr. Pat Sawyer. However, Shepherds for Sale also has many downsides, which I’ll turn to in the second half of this review.

But first, I need to make a brief digression.

Interlude: Equal Weights and Measures

One of the difficulties presented by the polarization of our culture is that people are generally unwilling to take sides against “their tribe.” But the truth must matter more than our tribal allegiances. Progressives may be content to adopt a relativistic standard of “your truth” and “my truth,” but Christians cannot.

According to the Westminster Larger Catechism, the Ninth Commandment forbids not just bearing false witness, but all acts that obscure or prejudice the truth. In other words, it is possible to violate the Ninth Commandment by making technically true statements that intentionally mislead hearers or by knowingly withholding counterevidence. These conditions are simply entailments of the Second Greatest Commandment: interpret others as you would want to be interpreted.

I’d like to illustrate these principles with the following excerpt from an imaginary review of Basham’s book:

“Progressive Anger: A Long Review of Basham’s Shepherd’s for Sale”

Megan Basham is a journalist with a long list of grievances against the disproportionately straight, White men who run theologically-conservative evangelical organizations like the Gospel Coalition, the SBC, and Christianity Today. There is hardly a single progressive talking point that doesn’t animate Basham: her book runs the gamut from racism to climate change to immigration to LGBTQ inclusion to the #MeToo movement. “Racism is real,” she proclaims on page 149. “It is ugly, and it should be opposed wherever it is found.” She continues: “The fact that white supremacist leaders like Nick Fuentes and Richard Spencer are attracting a large audience of young men is a legitimate crisis” (p. 150). She points out how capitalist demand for new technology has led to terrible working conditions as Africa is stripped of its natural resources: “cobalt… is being dug out of the ground by slaves in the Congo, including many children, some as young as four” (p. 30). She is highly critical of the late pastor Tim Keller, who appealed to his interpretation of the Bible to argue that abortion is a “grievous” sin (p. 59) and that “sexual morality cannot be dismissed as an issue on which Christians of good faith can agree to disagree” (p. 217). Elsewhere, she makes a list of Christian colleges that have taken steps toward LGBTQ affirmation: “Baylor, Azusa Pacific, Wheaton, and Calvin University are just a few who offer some level of accommodation, including allowing LGBTQ clubs and same-sex student romances” (p. 225). At one point, she even reproduces a prayer entitled “Woe to the Unholy Trinity”: “We renounce it. We repent of it. Unrestrained Capitalism, Consumerism, Individualism… This unholy trinity That oppress the poor, Ransacks the Earth” (p. 21) This book is revelatory for those who want a better understanding of Basham’s views on social issues.

Two things are true of this hypothetical review.

First, every statement in this densely cited passage is technically true and if you follow the page numbers, you will find every quote verbatim.

Second, this hypothetical passage would nonetheless be a gross violation of the Ninth Commandment. By omitting context and through clever framing, I have made it sound like Basham is a raging progressive. I have twisted accurate quotes and have highlighted certain points she made (e.g. “racism is real”), but used them to spin a false narrative.

These objections are 100% valid. If someone waved them away as “nitpicking” or “logic chopping” or “hiding behind technicalities,” they would be deeply mistaken. In the next section, I will ask the reader to apply precisely these same criteria to Basham’s book.

Misrepresentation

Based on their reactions, fans of Basham’s book were particularly impressed with the extent of her research, commenting on the sheer number and density of her endnotes (572 in total, taking up 52 pages at the back of her book). But critics soon began sifting through these endnotes, calling attention to numerous alleged errors [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][review][review].

Many of these errors were minor (e.g., misstating where two pastors had gone to seminary) and Basham acknowledged some of them. However, others were more serious and I’ll discuss a handful here (unfortunately, there were quite a few).

Two words of caution:

First, I am not claiming that these misrepresentations are intentional. There are many ways an author can inadvertently misrepresent a quotation.

Second, I am not claiming that these misrepresentations disprove the book’s central thesis. However, contrary to claims I’ve seen on social media, they are also not unimportant, as I’ll explain at the end of this section.

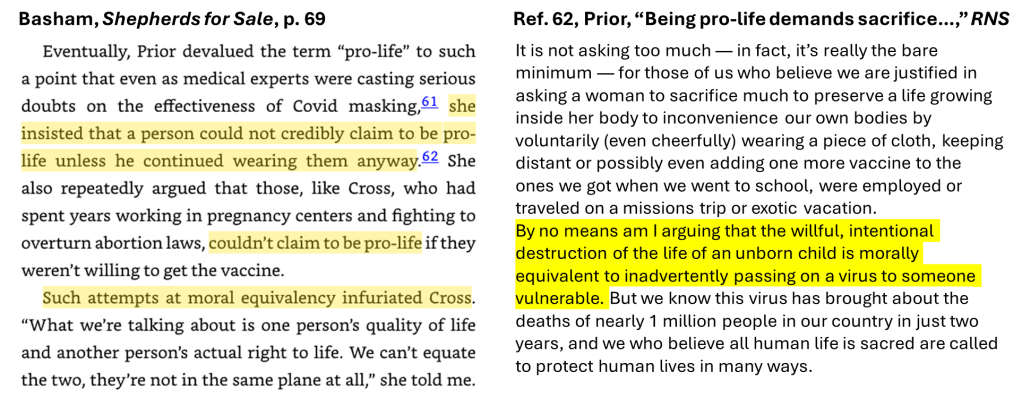

First, in Chapter 3 “Hijacking the Pro-Life Movement,” Basham worries that all kinds of progressive causes are being annexed to the pro-life cause, thereby diluting it. I share this concern. For example, pro-life evangelical literature professor Karen Swallow Prior posted irate and rightly-criticized Tweets lambasting pro-lifers for their failure to support COVID protocols. However, in chapter 3, Basham cites a 2022 RNS article by Prior and makes several claims about it. First, she writes that Prior “insisted that a person could not credibly claim to be pro-life unless he continued wearing [masks]” and that she “repeatedly argued that [pro-life activists] couldn’t claim to be pro-life if they weren’t willing to get the vaccine.” Then she characterized Prior’s reasoning as an attempt at “moral equivalency” (p. 69).

However, the article in question supports none of those claims. Prior argues that opposition to abortion “is founded on the desire to protect the lives of the innocent and vulnerable” and that pro-lifers therefore ought to wear masks, even though she grants that “the science about masking, social distancing and even vaccines” is not “entirely conclusive [or] indisputable.” However, near the end of the essay, she explicitly states: “By no means am I arguing that the willful, intentional destruction of the life of an unborn child is morally equivalent to inadvertently passing on a virus to someone vulnerable.” In precisely the same way, we can assert that our commitment to honesty entails that we shouldn’t embezzle $10 million dollars and also that we shouldn’t steal gum, without in any way implying that those actions are morally equivalent.

Just to be sure, I contacted Prior and she agreed that I had understood her argument. I asked her if she had ever believed or currently believed that non-maskers cannot credibly claim to be pro-life. She answered: “no.” I asked her: “Have you ever argued or do you argue today that those who had spent years working in pregnancy centers and fighting to overturn abortion laws, couldn’t claim to be pro-life if they weren’t willing to get the vaccine?” She replied: “Absolutely not.” None of the claims that Basham made about Prior are true, and none are justified by the article she cited.

Second, on p. 187, Basham discusses the impact of the #MeToo movement on the church. She writes:

One pastor, Todd Benkert, became so overt in this kind of brand building–plastering his survivor ribbon-themed convention booth across social media, organizing unofficial breakout sessions in which he positioned himself as an expert, leaking to the press complaints he was supposed to be investigating–that he had to be removed from the abuse task force altogether.[81]

Basham cites a 2023 RNS article to justify her claim that Benkert’s “brand-building” led to his removal. However, the article in question does not say that Benkert “had to be removed.” Instead, it states that Benkert “stepped down” and had “resigned.”

I contacted abuse task force chairman Marshall Blalock for more details. He wrote back: “Todd Benkert resigned after a short term on the Task Force. The ARITF was unanimous in thanking him for his service. Todd’s leaving was a strategic decision on his part to be more free to advocate for abuse reform in important ways outside of the task force. He remained supportive of the ongoing work of the ARITF.” He added that Todd had not been removed and that “his departure was not acrimonious.”

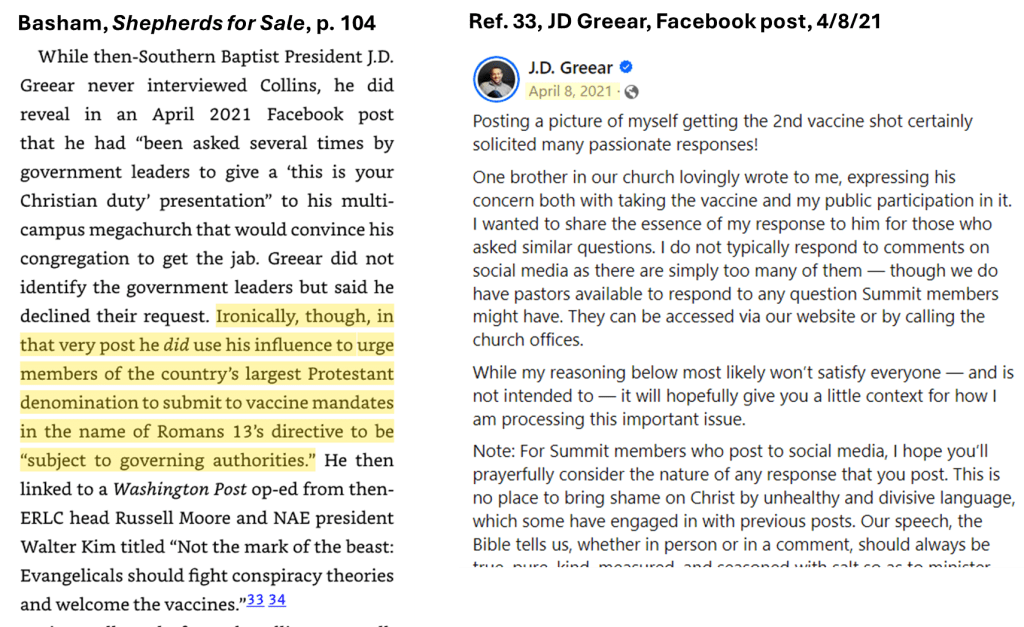

A third example involves my pastor J.D. Greear and his stance on COVID vaccines. On p. 104, Basham writes that in an April 2021 Facebook post, Greear used “his influence to urge members of the country’s largest Protestant denomination to submit to vaccine mandates in the name of Romans 13’s directive to be ‘subject to the governing authorities.'”

There are a number of problems with this claim, but I will only mention the most important one: the post in question was not about vaccine mandates. Greear repeatedly stated in the post that “there is certainly room in the body of Christ for believers to disagree [over the vaccine],” that the decision to not get the vaccine is “a matter of judgment and conscience,” and that it is not “a first order issue of faith.” He then explained how his own personal decision to get the vaccine was based on his belief that it is generally wise to “defer” to the government’s “counsel” and “recommendation.” In other words, he was not talking about a command from the government, but advice. Most importantly, however, Greear’s post was made on April 8, 2021. and federal mandates were not put in place until five months later as Basham herself affirms (p. 110). Thus, Greear could not possibly have been talking about “vaccine mandates” in his post, as Basham claims.

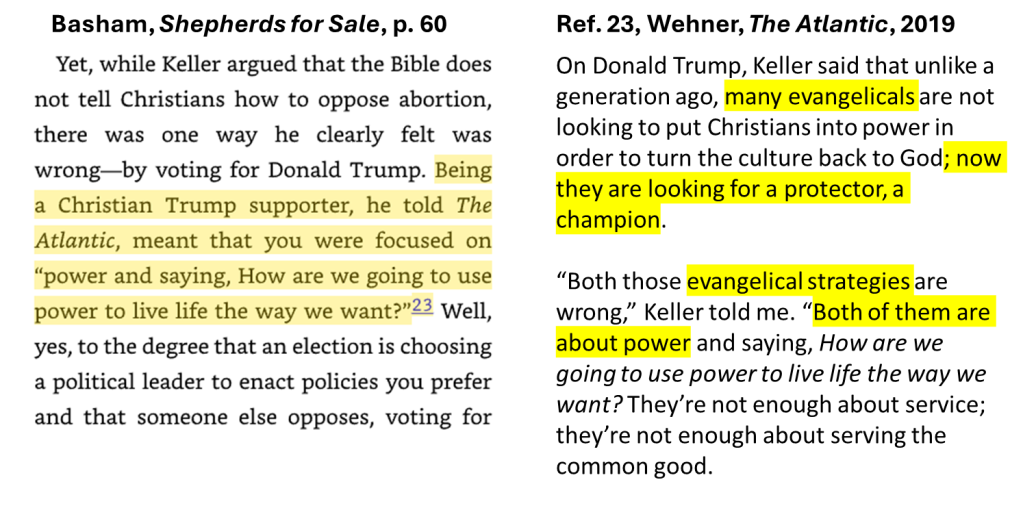

Finally, on p. 60, Basham claims that Tim Keller “clearly felt” that voting for Donald Trump was wrong and that “Being a Christian Trump supporter… meant that you were focused on ‘power and saying, How are we going to use power to live life the way we want?'[23]”

However, Ref. 23 is a 2019 Atlantic interview with Peter Wehner. In that interview, Keller does not say that “Being a Christian Trump supporter” means being focused on “power.” Rather, he is discussing two wrong “strategies” that “many” evangelicals employ. He argued that both strategies are wrong. In the same way, if I wrote that “Many Christians are looking for a church with a nice building or organ music, so they become Anglican. These strategies are wrong because they are about aesthetics rather than doctrine” it would be incorrect to claim that I am saying “Being an Anglican means focusing on aesthetics.”

Furthermore, Basham repeatedly claims that Keller singled out Trump voters for censure. She says that Keller found support for Trump “uniquely discrediting,” (p. 61) “denigrated the motives” of evangelical Trump voters (p. 61), characterized them as “power-driven” (p. 62), and showed them “disapproval” (p. 64). I could find no support for these claims in the articles she cited (see a short analysis here). Additionally, I searched Twitter to see how often Keller talked about Trump. In his 10 years on the platform, he used the word “Trump” only three times: Once to deny that he had ever made “never-trump” arguments. Once to deny that he had ever shamed Trump supporters. And once to call on everyone to fast and pray in response to an FBI warning about an “armed demonstrations” by pro-Trump protestors. Thus, Basham’s characterization of Keller is incorrect on multiple levels.

Based on what I’ve presented so far, what should we conclude?

Here, I’d like to quote Basham herself. On page 173, she argues that ERLC member Philip Bethancourt’s synopsis of five clips from a secret audio recording is inaccurate, especially when it comes to a single, key sentence. She concludes: “given how [Bethancourt] failed to accurately represent the most controversial clip… there’s reason to doubt his framing of all the snippets” (p. 173).

In other words, Basham believes that a misrepresentation of one clip calls into question the framing of all the others. Unfortunately, after finding multiple misrepresentations in Basham’s work, I reached a similar conclusion: she is an unreliable interpreter. While many of her claims may be true, I can’t assume that any quotation I find in her book has been represented accurately.

Oversimplified Narratives

Basham’s book is structured around a simple binary: there are good pastors and bad pastors, stalwart conservatives and squishy progressives, wolves and shepherds. Another binary is progressive drift versus conservative stability. Progressive institutions are corrupting pastors with money and prestige while conservatives are resisting this temptation.

However, both narratives are oversimplified.

For example, based on Basham’s evidence, progressives have indeed attempted to pull evangelicals left on immigration. But has it worked? The data is unclear. For example, the Evangelical Immigration Table, which seems to have received at least indirect funding from George Soros, was founded in 2012. A series of polls and surveys have been conducted over the last two decades asking slightly differently worded questions about evangelical support for a pathway to legal status for illegal immigrants. Yet these surveys do not show a clear shift in these attitudes with the advent of the EIT. Similarly, the SBC passed resolutions on immigration in 2006, 2011, 2018, and 2023, which are all very similar. If anything, the most recent SBC resolution was more conservative than the previous ones. These data should lead us to ask whether all the Soros dollars that are supposedly corrupting evangelicals have had any effect at all over the last decade.

Or consider Basham’s claim that after the Supreme Court struck down Roe vs. Wade, “many of the big-name evangelical leaders who were supposed to represent pro-life activists… sounded distinctly less than celebratory” (p.52). She names Russell Moore, Beth Moore, Karen Swallow Prior, and Mika Edmonson as those who offered problematic responses. But what about other members of “#BigEva”? Brent Leatherwood, J.D. Greear, Gavin Ortlund, and The Gospel Coalition all immediately posted celebratory tweets or articles. Again, I’m not disagreeing that some evangelical responses were muted or underwhelming (although I think the criticism of Prior’s NYTimes article is arguable). Instead, I’m pointing out that, with so many characters within the orbit of #BigEva, it’s easy to craft whatever narrative we want.

Conversely, Basham’s narrative is also incomplete because it focuses almost exclusively on progressive organizations who attempt to purchase evangelical loyalty. But isn’t it also true that groups on the Right are competing for evangelicals’ allegiance? For example, the right-wing organization Turning Point USA hosts a pastor’s conference each year, with an explicit goal of highlighting “the need for pastors and their congregations to stand for truth and no longer let culture in America dictate the terms in which the Church can exist.” But the speakers’ theologies are all over the map, from Reformed Baptists (John Cooper), to New Apostolic Reformation advocates (Ché Ahn, Lance Wallnau), to an atheist (James Lindsay). Obviously, TP-USA is not trying to explicitly undermine evangelical beliefs on sexuality. But is there not a temptation to sweep serious doctrinal differences under the rug for the sake of sociopolitical co-belligerency?

The takeaway is that cultural pressure is always contextual. Can evangelicals be hesitant to speak the truth in love because it will be unpopular with MSNBC viewers? Yes. Can evangelicals also be hesitant to speak the truth in love because it will be unpopular with Fox News viewers? Yes.

The popularity of Basham’s book is itself evidence that success, fame, and money can be obtained not only by punching right but also by punching left. Should we conclude that Basham doesn’t actually believe what she wrote and was motivated solely by self-interest? Absolutely not. But we should conclude that money and acclaim tug at us from both directions.

In conclusion, let me return to the point I made in the interlude: if you do not interpret others the way you want to be interpreted, you are violating the second greatest commandment. If you would rage at someone who took Basham’s words out of context, claimed that she said things she didn’t actually say, and put the worst possible spin on all her actions, then this is the standard to which you are also accountable. The Ninth Commandment applies to everyone, everywhere, all the time.

Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, I’d like to first address critics of Basham’s book (especially those who would align with #BigEva):

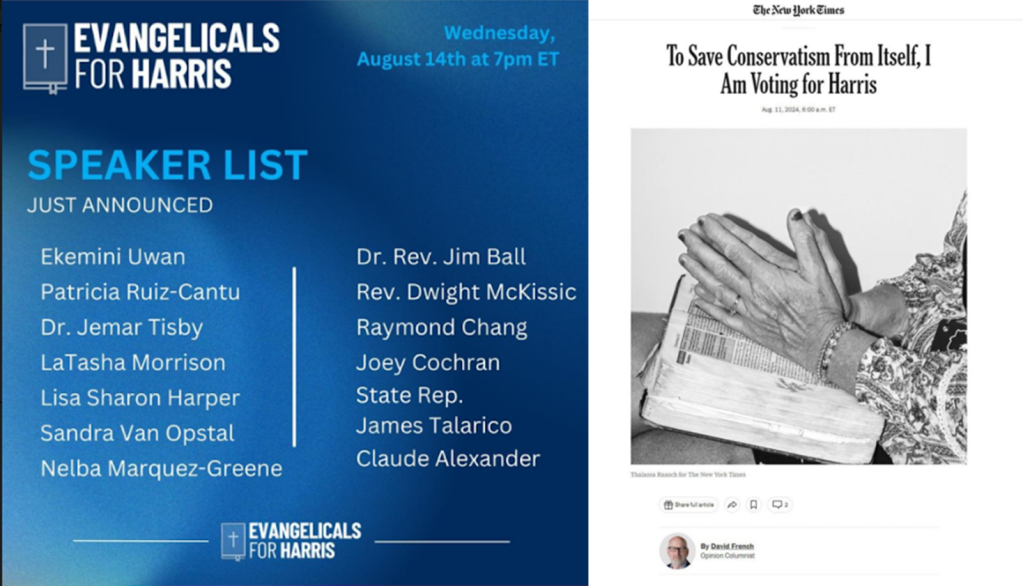

As I’ve shown in this review, some of Basham’s criticisms are inaccurate or unfair. But not all of them are. Two weeks after Basham’s book was published, a group called “Evangelicals for Harris” and political commentator David French were kind enough to run a marketing campaign on her behalf, showing exactly why so many evangelicals are rightly concerned.

Some evangelicals are indeed drifting (or hurtling) leftward. Some COVID responses were mishandled. Critical race theory and queer theory have been coddled. It’s time to be honest about that. Don’t hide behind this book’s errors to dismiss it altogether. If you made mistakes, own them. Do so whether or not your critics will rejoice, whether or not they will capitalize on your admissions, whether or not they are hypocrites who refuse to admit their own failings. You stand or fall before God alone. He has forgiven you, so be honest with Him, with yourself and with others.

To fans of Basham’s book, I know that many of you have been longing for #BigEva to receive its comeuppance. Maybe you lost your job over vaccine mandates. Maybe you watched wokeness devour a church you loved. Maybe you’re tired of seeing celebrity pastors catering to progressive sensibilities while sneering at the concerns of fellow believers. As you read Shepherds for Sale, you think: “finally, someone is going to take a flamethrower to this den of thieves! Now is not the time to quibble about a few details!”

I understand this mentality, but it is exceptionally dangerous. C.S. Lewis warns:

Suppose one reads a story of filthy atrocities in the paper. Then suppose that something turns up suggesting that the story might not be quite true, or not quite so bad as it was made out. Is one’s first feeling, ‘Thank God, even they aren’t quite so bad as that,’ or is it a feeling of disappointment, and even a determination to cling to the first story for the sheer pleasure of thinking your enemies are as bad as possible? If it is the second then it is, I am afraid, the first step in a process which, if followed to the end, will make us into devils. You see, one is beginning to wish that black was a little blacker. If we give that wish its head, later on we shall wish to see grey as black, and then to see white itself as black. Finally we shall insist on seeing everything — God and our friends and ourselves included — as bad, and not be able to stop doing it: we shall be fixed for ever in a universe of pure hatred.

Truth still matters. Even if you wholeheartedly believe that #BigEva needs to be destroyed, you cannot turn a blind eye to factual errors in Basham’s book, especially since they pertain to the actual character of actual people.

As someone who is #BigEva-adjacent, I understand your frustration. When you see a clip of SBC president J.D. Greear preaching “God whispers about sexual sin,” you’re ready to tap out.

You long for a pastor who will simply read Romans 1 to his congregation: “their women exchanged natural sexual relations for unnatural ones. The men in the same way also left natural relations with women and were inflamed in their lust for one another. Men committed shameless acts with men and received in their own persons the appropriate penalty of their error.” A pastor who will argue against revisionist views, pointing out that Paul does not distinguish between different kinds of homosexual acts and identifies all sexual relationships of men between men and women between women as a departure from the Creator’s design. A pastor who will warn the church that downplaying the sin of homosexuality won’t win the next generation and that removing the offense of the cross divests it of its power. A pastor who insists that the Bible’s condemnation of homosexuality in passages like 1 Cor. 6:9-10 is God’s gracious word of warning to a perishing world.

Where are pastors like this who will simply speak the truth in love?

This may come as a shock, but those aren’t my words. The statements in the previous paragraph were all made by J.D. Greear, in his (infamous) 2019 sermon “How the Fall Affects Us All” and then later in a 2023 article he wrote for The Gospel Coalition, opposing Andy Stanley’s revisionist views on sexuality.

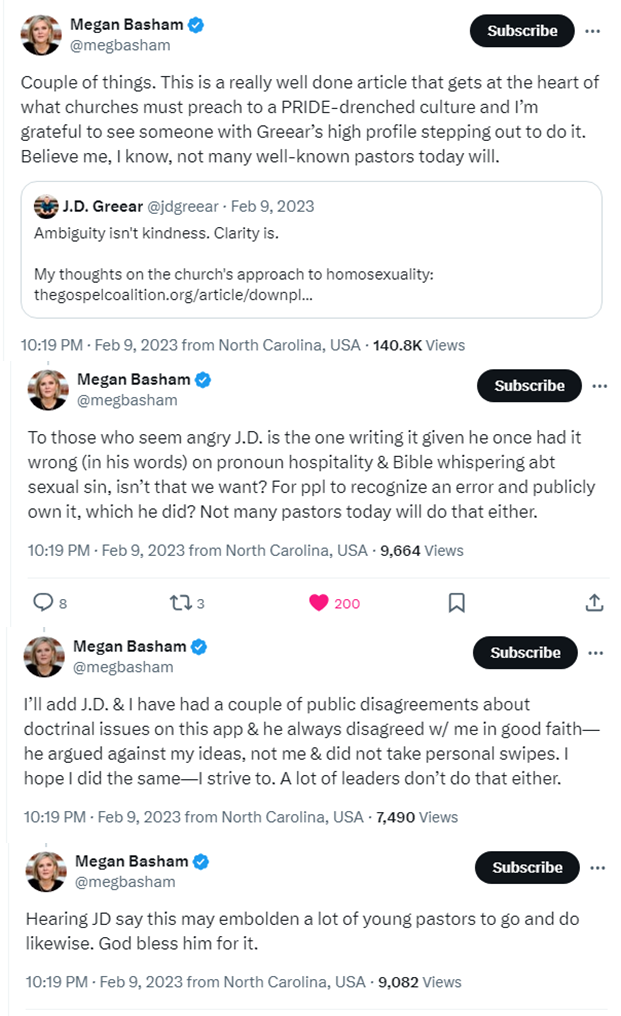

To those who seem angry at J.D., given that he once had it wrong (in his words) on pronoun hospitality and the Bible “whispering about sexual sin”: isn’t that what we want? For people to recognize an error and publicly own it, which he did? Not many pastors today will do that. Hearing J.D. say this may embolden a lot of young pastors to go and do likewise. Our response should be: God bless him for it. J.D. and I have sometimes disagreed, but he has always argued against my ideas, not against me and did not take personal swipes. I hope I did the same—I strive to.

Doesn’t that sound reasonable?

This may also come as a shock: the words from the previous paragraph aren’t mine either. Those statements were made by Megan Basham on Feb. 9, 2023.

War is a serious thing. War between brothers and sisters in Christ is even more grievous. Before we grab our pitchforks and burn down the institutions, let’s weep, pray, and maybe pick up the phone.

Related articles: