In Trump’s America, you could easily imagine finding a diatribe like this one on a Reddit thread or 4chan message board:

“Black nationalism is a racist ideology that is based upon the belief that black people are superior in many ways to people of other races. This thread will help black people understand and take ownership of their participation in black nationalism. This is truth work. Tell the truth as deeply as you can. No side stepping or surface skimming. If you go deep, if you tell the real, raw, ugly truths, you can get to the rotten core of your internalized black nationalism. When you don’t tell the truth as deeply as you can, you are cheating yourself of your own growth, and illustrating that you are not truly committed to dismantling black nationalism within yourself and therefore within the world.

This work is hard. Black nationalism is an evil. The process of examining it and dismantling it will necessarily be painful. It will feel like waking up to a virus that has been living inside you all these years that you never knew was there. And when you begin to interrogate it, it will fight back to protect itself. You will want to blame me, rage at me, discredit me, and list all the reasons why you are a good person. That is a normal, expected response. That is the response of the anti-Whiteness lying inside. You have to understand this before you begin.

You [need to] rehumanize yourself. You had shut down a part of your humanity in order to participate in black nationalism.

Here are a few examples of black fragility in action: Getting angry, defensive, or afraid; arguing, believing you are being shamed, crying, or simply falling silent. In essence, black fragility looks like a black person taking the position of a victim when it is in fact that black person who has committed or participated in acts of racial harm.

The most extreme manifestations of black nationalism are the Nation of Islam or the Black Hebrew Israelites. But just because these are extreme does not mean that lighter versions of this ideology do not exist at more unconscious levels for progressive, we-are-all-one-race, peace-loving black people. You do not have to buy into this extreme ideology to harbor thoughts of black nationalism. Again, it is important to stress that this belief is not necessarily a consciously chosen one. It is a deeply hidden, unconscious aspect of racial supremacy that is hardly ever spoken about but practices in daily life without even thinking about it.

‘They can’t mean me! I voted for Clinton. I have White friends. My kids play with white kids. I’m one of the goods ones.’

Sound familiar? None of these things that you have confidently declared as evidence that you are not racist erases reality. You have been conditioned into a black nationalist ideology, whether you have realized it or not. Black exceptionalism is the idea that you are somehow special, exempt, above this, past this. You are not. You are not an exceptional black person, meaning you are not exempt from the conditioning of black nationalism, and from the responsibility to keep doing this work for the rest of your life.“

That someone could pen this screed on the internet is, sadly, not surprising. But what if I told you that these comments were taken from a best-selling book that was lauded and praised by numerous right-wing celebrities? Are you appropriately appalled? Are you sure? Because this tirade was extracted from a 200-page book filled with similar musings and was indeed published and celebrated.

Sort of.

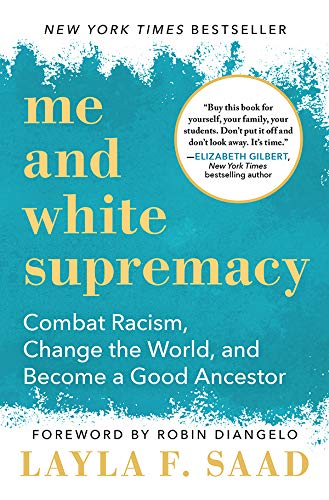

What you just read was a series of nearly verbatim quotes from Layla Saad’s Me and White Supremacy (p. 12, p. 3, p. 14, p. 18-19, p. 25, p. 42, p. 61-62, p. 69-72) with the modification that I reversed the roles (e.g. substituting “black” for “white” and “black nationalism” for “white supremacy/superiority”). At this point, we have to ask ourselves a serious question: why is this kind of writing permissible and even laudable when applied to whites but not when applied to blacks?

Equal Weights and Measures

The immediate response to this question is that Saad’s stance is acceptable because of the history of racial oppression in the United States (and, apparently, Qatar, where Saad lives). A symmetric standard that holds Black and Whites to the same norms of discourse and charity is inappropriate in light of historic and present-day white oppression. In the same way, if a man has been unrepentantly beating his wife for decades, a marriage counselor who rebukes the wife for being “too angry” is wildly out of line. An asymmetric treatment and evaluation of their roles is completely legitimate in light of their history.

This response, though common, has several problems.

First, a moment’s reflection shows us that it is simply not true that the average black person stands in the same relation to the average white person as an abused wife stands in relation to her abusive husband. For starters, the “average black person” and the “average white person” have never even met. So to argue that it is legitimate for a particular black person to treat a particular white person –or white people in general– as if they were the perpetrator of abuse is to argue it is legitimate to make negative evaluations of someone based on their race alone. Until very recently, making such generalizations and prejudgments was the definition of racism.

Yet Saad’s book is suffused with such prejudgments. It forms the basis for her constant admonitions that white people have unconsciously adopted the belief that “people with white or white-passing skin are better than and therefore deserve to dominate over people with brown or black skin” (p. 60-61) that they believe in “[their] own and other white people’s superiority over BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Color]” (p. 65), that they have been “conditioned into a white supremacist ideology, whether [they] have realized it or not” (p. 69), etc… So we’re going to have to decide, as a culture, whether or not we will embrace or repudiate the idea that we should judge a man by the color of his skin rather than the content of his character.

Second, even if this analogy were true in general (and it is not), Saad’s reasoning would still be dangerous because it makes disagreement impossible. She not only assumes that all whites subconsciously believe in their racial superiority, but also insists that any disagreement with this claim is merely a way for whites to avoid admitting their true beliefs and “doing the work” of antiracism. Were we to turn the tables (as I did in the first section), we would immediately recognize this approach as a horrifically abusive kafkatrap.

Finally, if we were to accept such reasoning, it is hard to see how we could ever apply universal moral or biblical standards to anyone’s behavior. How can we urge Christians to “think of others more highly than themselves” (Phil. 2:3) while also permitting BIPOC to impute deeply racist beliefs to White Christians? How can we tell Christians to “put away all anger and slander” when this admonition would be dismissed as “tone policing” (p. 46-51)?

Over the last few years, I’ve read many terrible books rooted in critical race theory, but this one stands out. I am continually amazed that Whites seem so eager to embrace these ideas in a kind of performative, self-flagellating allyship (which is problematic – see pages 155-161). I can only speculate that some Whites truly believe that adopting this framework will lead to racial unity. But it won’t. It will only lead to anger, bitterness, and paranoia, symptoms which are amply attested in the outlook and affect of its adherents.

To urge or allow others to drift into this ideology is not empathetic; it is unloving. Fashionable nonsense is still nonsense and fashionable racism is still racism.

See all content on critical theory here.

Related articles: